Stagenoise in Paris

Staying in a part of Montmartre where the film Amelie was filmed, I thought the most I would recognise was the Art Nouveau metro station entrance, but within a couple of days I had spotted one of the leads from the film, a short, stubby nosed, rather gargoyled looking man who also appears in Jeunet’s next film,A Very Long Engagement. I saw him again on several occasions, doing his shopping, so he was obviously a local. Amelie had quite an impact on the already tourist-magnet neighbourhood. Now various food shops are known as "the fruit tart shop in the film" etc. Happily, it has not given anyone a reputation they don’t already deserve – the fruit tarts are a destination in themselves. (Les Petits Mitrons, Rue Lepic, if you must know).

I had hoped to see a new work by Ariane Mnouchkine at the Theatre du Soleil but she delayed the opening by three weeks, so instead I went to see the latest offering at the Bouffes du Nord from Peter Brook, based on the novel Life and Teaching of Tierno Bokar – The Sage of Bandigara by the African writer Amadou Hampaté Bâ.

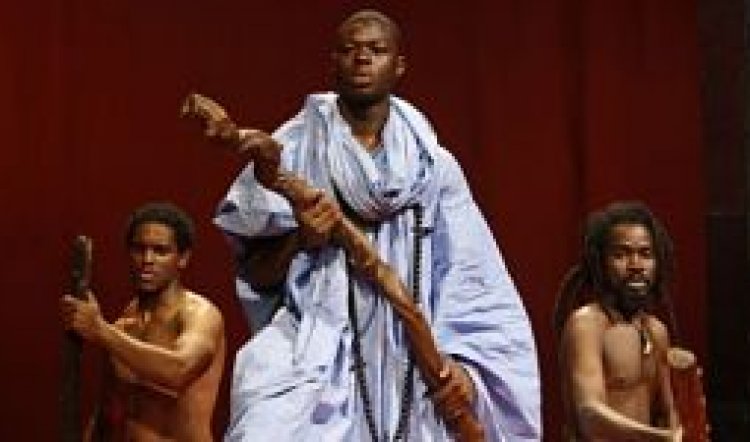

The short play, (90 minutes) Eleven and Twelve, is touring to the STC in June as part of an extensive world tour which takes in the Barbican in London and the Wellington Festival. It’s a very travel-friendly piece, with a small cast and a very modest set, consisting of a piece of coloured cloth and those distinctive carved tree trunks that serve as ladders in Mali, where the play is set.

Very much part of the continuum of the style of Poor Theatre that is the signature of Brook’s work, and also consistent with his anthropological, political and sociological preoccupations as themes of exploration through story telling, Eleven and Twelve is a fable. It hinges on the Muslim observance of prayer being repeated either eleven times, or, following a human glitch, twelve times. That innocent break with custom is enough to cause division in a previously harmonious community and to cause conflict and unrest with French colonial masters, causing grief, loss and exile.

The play is performed in English in a series of vignettes, but is not really a piece of theatre so much as a philosophical debate about belief, racism and colonial power. Many of the scenes are very static, apart from one exquisite moment of invention when a journey by sea is created simply by two men twisting up the cloth on the ground to fashion a small boat and rocking it gently from side to side. There is a lot of talk and very little action and the talk is very abstract, like a gentle meditation. As a play, it follows a slower rhythm than we are used to in traditional Western theatre. There is nothing wrong with sitting in a beautiful space and slowing down to a different pace for a performance if it takes you somewhere new. Ultimately Eleven and Twelve feels unsatisfying because it lacks drama. I could have read it and got just as much, or as little, from it.

In total contrast, something I could not have read was the new show from Zingaro, a troupe who defy easy labeling but call themselves performers of Equestrian Opera. Sounds insufferable, but it isn’t. Since they burst on to the scene 25 years ago as a dubious band of gypsies under the leadership of a bald tattooed man calling himself Bartabas, Zingaro have been unrivalled in their flamboyant display of horsemanship as performance, accompanied by wild live gypsy music, played by troupes from all over the world. The result has always been thrilling, edgy, fast and furious. It is not circus, not cabaret, but it is always a celebration of the horse/human connection in some poetic, romantic and original way.

-c750x442.jpg)

I have been an unashamed Zingaro follower for years, but they are hard to catch as mostly their shows are on tour in Japan (where they have a devoted following and rich sponsors) and California where, following an appearance at the LA Olympic Arts Festival, they are regulars. Because of its quarantine laws and the prohibitive costs involved, Zingaro will never come to Australia, although I have heard several festival directors acknowledge the company as top of their wish list.

But this is one theatre it’s worth making a pilgrimage to see: it’s in a converted military fort on the outskirts of Paris at Aubervilliers. The company and its unusual space were funded through one of the most enlightened and progressive cultural initiatives of the Mitterand government, under the auspices of minister for the arts Jack Lang, who personally spearheaded the renaissance of circus and related performance. Now, within the fort’s walls, there is a wooden theatre, which looks like a Russian church. Stables lit with chandeliers form part of the theatre, while, across a courtyard, a massive wooden Mongolian yurt spread with carpets functions as bar and restaurant space. It’s a very seductive setting in an otherwise unprepossessing suburb.

So you can imagine how it breaks my heart to have to tell you the latest show, Darshan (a Sanskrit word that refers toa vision but is used here to evoke a spiritual journey) is lame. Instead of the usual close contact between riders, musicians and the audience seated in a traditional ring, Bartabas has chosen to reverse the configuration of the performance, placing the audience in the centre, on a slow moving revolve, gazing out to a ring of sawdust and beyond to a scrim. On the other side of the scrim horses move past as shadows, interacting with various riders and acrobats. Sometimes, but only too rarely, the horses suddenly appear, riderless, through parting screens for a dazzling canter around the ring, manes and tails flying, like wild and mythic beasts. For a brief moment there is the potential for magic, but it does not last. The shadow play idea is a thin, simplistic one, just a visual trick, really, not a concept that can carry 90 minutes of audience attention. There is certainly none of the wonder and majesty that previous shows have evoked. Most sequences go on way too long, some digital images used to enhance the action become unendurably tedious. To add to the misery, Bartabas has substituted taped music for live performance, further reducing the vitality and spontaneity that were hallmarks of previous productions. It’s slow and joyless. The half-hearted applause at the end was a clear indication of tedium and disappointment and the remarks I read online later reflected my own.

So, this is not the year to see Zingaro, but it’s still worth making a note of the company’s name and giving them a second chance once this production has well and truly bolted from the stable.