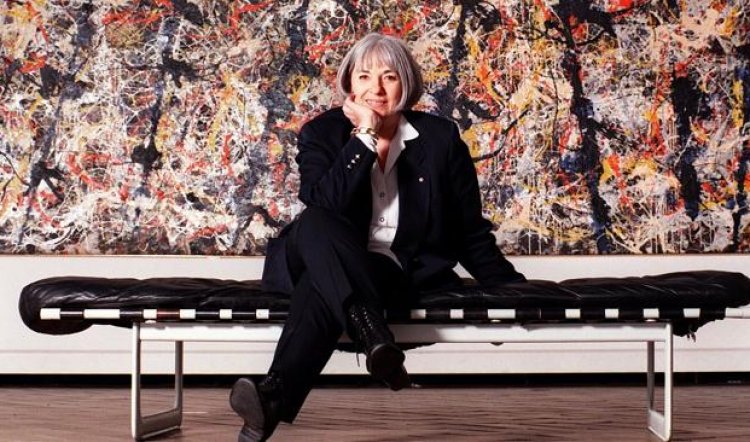

BETTY CHURCHER 1931-2015

Better Churcher was one of the true greats of Australian art and culture. She wanted people to understand and share her own passion for art and she achieved that through her work first as an educator and as Director of the National Gallery of Australia; through her two ABC TV series, Take Five and Hidden Treasures. And, more recently, with her two volumes of sketches of her most-loved great works from around the world published as Notebooks, in which her own always-downplayed talent as an artist became clear for all to see and enjoy. In everything she did, she was a great communicator.

Born Elizabeth Ann Cameron in what was then a semi-rural part of Brisbane, her keen eye for nature and beauty is evident in a memory she recalled for Robin Hughes in the Australian Biography project interviews. She described a creek that formed the boundary of the family home:

“...it was the most magical creek. It was one of those lovely little creeks that had crystal clear water and that green, cow cropped grass going right up to the edge.

“And every now and then, a little bit of, ah, the bank would break away and become a little island, topped with this lovely little pad of green grass. I used to sit on that, and just watch the water run by and dream, and that was really probably one of my favourite spots.”

A child of the Great Depression and then of the Second World War, Churcher’s most vivid memory of the latter was how unfair it was that the local shop displayed Cadbury’s Chocolate packages in its window – but they were empty because of rationing. More significantly, however, real deprivation came for young Betty when her strictly traditional Scottish father told her that school was over after Year 10.

“...he decided that I should leave at Grade 10, which is like the Intermediate. And I desperately wanted to go on. I knew that I really truly wanted to go on to Senior, or HSC, you know, ah - university qualifying. And he made this very, very puzzling comment to me. He said, ‘Look, Betty, it won't be useful. You'll only get married. You won't need an education’.

“He said, ‘It spoils a girl’. And I remember thinking,’How can it spoil a girl?’, you know? Because I was too young, really, to get what he was talking about. What he was talking about is that it'd give me aspirations and ah, hopes and ambitions that perhaps, you know, might spoil it for somebody who wanted to have his tea made for him every morning, noon and night.” (Earlier in this interview with Robin Hughes she had described how her mother did everything in the home so when she was ill, she had called upon her daughter to drop everything – including small children – and go round to make her father a cup of tea, because he didn’t know how to. Not surprisingly, Churcher herself could do pretty much anything.)

What she did do was become a school art teacher and eventually marry painter Roy Churcher. She had already put her own ambition to be an artist permanently on the back burner. In her view she didn’t have what it took to be a great painter and rather than be a disappointment to herself, she set about supporting her husband and giving birth to and raising four sons.

Nevertheless, when the youngest started school she went back to work in a secondary school and along the way wrote a text book. Understanding Art was published first in Australia, then in Britain where, in 1973, it won The Times prize for Information Book of the Year. It changed everything. Her childhood thirst for education and academe was reawakened and she began writing art criticism for the new national paper, The Australian, while undertaking an MA at the Courtauld Institute.

Back in Australia and in 1982 she was appointed Dean of the School of Art and Design at the Phillip Institute of Technology in Melbourne – the first female head of a tertiary institution in Australia. Another first for women followed in 1987 when she became Director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia. Then, in 1990 she became the second Director of the Australian National Gallery in Canberra, after James Mollison and therefore its first female head and – within a very short space of time – the public face and household name of fine art in Australia.

Churcher was an irresistible mixture of brains, charm and steel. She was dubbed “Betty Blockbuster” for her determination and expertise in assembling the kinds of exhibitions that had people queueing to get in. Telegenic, articulate and warm, she singlehandedly turned around the image of the federal capital from a dull backwater and joke to a city whose tourist industry blossomed and boomed with car, coach and planeloads of interstate visitors heading for what she had renamed the National Gallery of Australia.

Betty was no mere pop-star, however, she attracted great borrowings from around the world, a multi-million dollar US donor fund and some fine minds, most notably the much admired Michael Lloyd whose premature death robbed the Gallery and Churcher of her probably successor. Neither was she deterred by some detractors who looked askance at the showbiz-style attention she attracted with the international shows. Asked about the grumblings, by a Fairfax reporter in 2011, she said, "Why I think it's so wonderful is we can never, in this country, own a lot of those great masterpieces, because we started too late, for one thing, so by the time the Australian gallery started, the European galleries had stuffed their cellars full of all the great masterpieces."

She was hugely successful in persuading those galleries to temporarily part with many of those great masterpieces, notably Masterpieces from Paris, a show that broke attendance and revenue records in 2010 and set a benchmark of excellence.

Her tenure was extended when a suitable replacement couldn’t be agreed upon and during her time the last great Heidelberg School picture still owned privately came up for sale. Golden Summer, Eaglemont, by Arthur Streeton had a price tag of $3.5 million. Betty hung it in the foyer of the Gallery and asked visitors to contribute. Like many other visitors, I tipped in my $100 and also like those others, received a personal letter from the Director thanking me – we all owned the picture now, was the message.

When Churcher finally left the Gallery it was not to retire. She and husband Roy moved to a lovely house and vineyard just north of Canberra and while he still painted, she was much in demand as a talking head, academic and then a bona fide TV star. She chatted to the ABC cameras as if they were old friends and the series Five Minutes (the running time, just before the evening news) was really how long she needed to introduce the audience to some minor art miracle she wanted to share.

It was followed in 2008 by Hidden Treasures. Each five minute episode of that series featured something marvellous she’d found in the collection of the National Library. The two series were a natural continuation of something she’d begun at the National Gallery where, in an out of the way corner, one might come upon an unheralded mini-exhibition of an obscure or not particularly popular artist that she wanted to quietly bring to the attention of visitors.

It was where I first saw a grouping of the works of Clarice Beckett and, as Churcher said at the time, “I like people to be able to discover things for themselves and she’s an artist worth discovering.”

Ironically, even as she herself was rediscovering her own talent and enjoying it in the making of her Notebooks, Churcher also discovered that her eyesight was failing. In the Australia Biography interviews she had said of her earliest experience with pencil and paper, “I just could draw. I was a bit like a child who's got, you know, perfect pitch. You think everybody's got it. And kids would say, ‘I can't draw’, and I thought – that's ridiculous. ‘You can see, therefore you can draw.’” And she did, as the Notebooks so intelligently demonstrate, to the delight of fans who listened to her at the Sydney Writers Festival in 2011 when she was on the road to sell her wares, as so often during her long career. And this was a woman who’d told Robin Hughes, “I don't know that I ever thought of making an actual living from art, to be perfectly honest.”

Talking to ABC TV 7.30’s Leigh Sales earlier this month she made it clear that she was unafraid of death, and also because the liver cancer was painful and inconvenient, she wanted it to come sooner rather than later. She said to Sales: "I do know I've had a very long and fruitful life. A whole lot of people die in their 20s and 30s and 40s - now, they’re the ones to feel sorry for, not 84-year-olds."

Betty Churcher was a wonderful woman, an easy companion and thrilling teacher; always an inspiration, a delight and a jewel in the crown of Australia’s art life. Rest in peace.