Love Lies Bleeding

Love-Lies-Bleeding, Wharf 1, Sydney Theatre Company, July 12-September 2, 2007

It is a rare and wondrous arts sponsor who not only obviously loves the sponsored form (in this case theatre and Sydney Theatre Company in particular) but also understands its product well enough to encapsulate its meaning in the opening words of his opening night, after-show speech.

Tony Scotford, former chair of STC and senior partner of company patrons, the law firm Ebsworth & Ebsworth, said of Don DeLillo's play Love-Lies-Bleeding: "Plays are about life and life is about what we are prepared to face up to."

What has to be faced up to, in life and in this new (2006) play, is the one great sure thing: death. It's something our modern, western, secular society isn't very good at. We shy away from it and, in these days of cosmetic surgery and personal trainers, expend ridiculous effort and energy on attempting to head off the inevitable.

Yet, even before the play opens DeLillo insists we look at it. Centre-stage in a dazzling white, New Mexico desert setting is Alex, a famous artist and man of four wives and much notoriety. Now, with all vigour and passion spent, he is reduced to a comatose, drip-fed cipher state, in a wheelchair, more dead than alive but still obstinately and steadily breathing.

"Persistent vegetative state," his son Sean tells Toinette, Alex's second wife and the obvious dominatrix of the family. Sean has a file of material, downloaded from the internet, on his father's condition and how to deal with it. He also has a bottle of morphine and a syringe. Sean and Toinette have come from New York, reluctant partners in a plan to euthanase Alex. But Tia, Alex's young and loving latest wife, says no, he's not ready to go while tenderly dabbing his lips with a water-soaked towel.

In a recent interview in The Age, DeLillo said, "I suppose this is a play about the modern meaning of life's end. When does it end? How does it end? How should it end? What is the value of life? How do we measure it?"

America's most abstract and admired poet of its way of life has made, in this play, a concrete, comedic work about these spectral dilemmas. Although at DeLillo's insistence there is little evidence of medical technology (the drip apparatus is the only visible connection between Alex and modern medicine), underlying the questions are those pertaining to medical "advances" and technology. Just because it is now possible to prolong "life", why is this seen as a good thing? Who does it benefit?

The impatient, rational Sean is adamant that Alex would not wish to continue as a vegetable. For all her acid wit and practiced ennui, Toinette is not so sure or keen to participate; and Tia is against it, but she too has a compromise threshold. Each occupies a cardinal point on the spectrum of contemporary opinion.

In flashback Alex lives in the form of veteran larrikin Max Cullen, from whom emanates an essential sense of why the three are drawn to the ghost-memory of his charm and powerful personality. As his living-dead self - Alex "in extremis" - Shaun Goss takes on what will probably go down as one of the most arduous roles of his (so far brief) career: not moving a muscle for close to 90 minutes.

Ben Winspear, best known in recent years as a director, imbues Sean with the abrasive edginess of a man unconvinced of his emotions and motives. Yet he is determined to do what has to be done and is paradoxically confident that his slim folder of downloaded wisdom will provide all the answers.

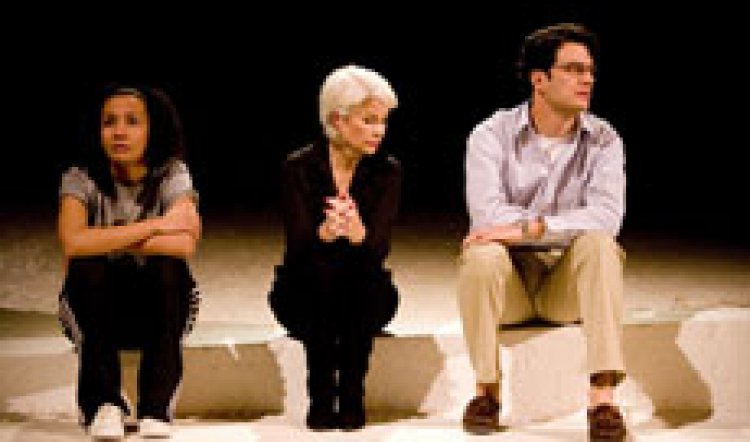

Nevertheless, the power of this production, directed with clarity and a sure sense of its drama and comedy by Lee Lewis, lies in the two women: spiky yet vulnerable Toinette (Robyn Nevin) and ostensibly softer but actually tougher Tia (Paula Arundell).

Arundell can do most anything she chooses, her range and intelligence make her one of the finest younger actresses on the Australian stage. In Love-Lies-Bleeding she turns in one of the most subtle and satisfying performances of her career to date as the seemingly naïve young wife and helpmeet to the ageing artist. Her interaction with Max Cullen is tender, touching and authentic, making sense of her later actions and raising vital doubts in the minds of the audience: what is "vegetable"?

Arundell is a perfect foil for Robyn Nevin's performance as the brittle, sharp-tongued Toinette. In her last appearance at STC before stepping down as artistic director, Nevin is a magnetic, crackling, sexy presence. She can do this kind of whip-cracking, wise-cracking role standing on her head, but that's not entirely it. She also injects pathos and uncertainty, hesitant gentleness and palpable fear into the character of the world-weary ex-wife and makes her a three-dimensional person rather than a merely clever comedy turn.

Fiona Crombie's stark white sand set works well in the Wharf space, while Luiz Pampolha's lighting is dramatic but (on opening night) the cues were either too tricky or not yet fully under control. The same goes for the pace of the piece: a little too stately and reverent, but likely to sharpen up with a few performances. Paul Charlier's soundscape evokes the inner journey of imagination as well as marking the passing of time and mood.

All in all, for a play which essentially re-asks: Whose life is it anyway? Love-Lies-Bleeding is simultaneously funnier and sadder and more profound than one might at first anticipate. Great choice by The Boss for her swansong, both as a play and a role. She's talking about not thinking she can or wants to act any more. Yeah right.