The Removalists

Classic, as a description, is tossed about way too lightly in referring to a play or movie, frock or song that we may have seen or heard of before. In this context it can mean older than last week, dated but quaint, my mum loved it, or something I think I should know about but don’t.

In truth “classic” should be confined simply to works that stand the test of time and still resonate 30, 100 or 300-plus years after their creation. It would cut down the number of candidates quite considerably, but David Williamson’s The Removalists would still be there.

When the play made its debut in Melbourne (La Mama) in July 1971 and at Nimrod (now the SBW Stables) in Sydney three months later, it was both original and shocking for audiences – in concept, language and “Australian-ness”. At that time Summer of the Seventeenth Doll was the closest audiences had come to seeing real Australia portrayed on a stage; and theatre in general was still not over being a poor cousin to London’s West End. It’s almost impossible to imagine now.

Nevertheless, it’s what made David Williamson such an astonishing phenomenon at that moment: with both The Removalists and Don’s Party bursting like monstrous NYE bungers across the snoozy firmament of White Australia’s dreamtime. These were audiences that had been raised on polite drawing room comedy and nice three act dramas, set in the Home Counties and performed by thesps who declared themselves to be “veddeh veddeh heppeh” to slum it in the colonies.

The very idea of hearing an Australian accent on a stage at that time was enough to send the homegrown Hyacinth Buckets into terminal tizzies. So that nice young Mr Williamson caused an unprecedented stir with his ocker types: attacks of the vapours in all directions. The funny thing is, The Removalists is still shocking now, but for different reasons.

In the play Williamson was observing and skewering a number of things about Australia that he didn’t much care for. Beneath the simpering good manners of polite society he detected several kinds of unpleasantness: domestic violence, corruption, hypocrisy and, just a scrape beneath the veneer of civilization, he posited that unbridled violence was lurking and waiting to pounce.

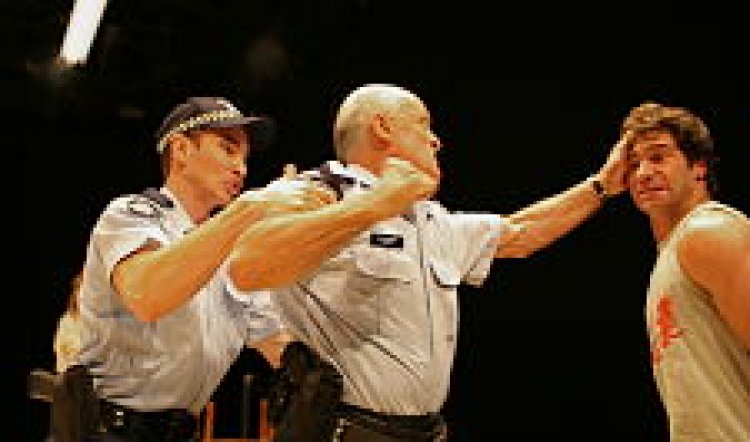

All of this happens in The Removalists and the shock to a 2009 audience is that it’s all so now. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Sergeant Simmonds (Danny Adcock) for instance, is a dead ringer for Chook Fowler, the venal old fart who starred in the Wood Royal Commission into police corruption. While Constable Ross (Dale March) is the epitome of the naive, well meaning, wet-behind-the-ears boy whose grip on his inner moral magnet is so tenuous that fear turns to savagery quicker than you can say “Carn, give him one, Rosco!”

This unlikely pair of Galahads set out to assist Fiona (Eve Morey) move out of her marital unit after she and her snobby elder sister Kate (Sacha Horler) front up at the backwater suburban sub-station to display Fiona’s lurid collection of bruises. These are the result of one row too many with her oafish hubby Kenny (Ashley Lyons). Fiona wants to take with her all the furniture she likes and Kenny apparently does not. A removalist is hired (Alan Flower) and an appointment made for Friday evening, when Kenny is always out drinking with his mates.

But as Tamie Fraser once so wisely said, “life wasn’t meant to be easy”. The plan, the true motives of all parties to the plan, and the ensuing black comedy of errors, are gradually upset and inverted, one by one.

The Removalists has a rich history and it’s to the credit of this cast and team of creatives that it isn’t allowed to hang over the production. Williamson himself has tinkered with the script, apparently, to bring it up to date. But it’s barely noticeable unless you know that the removalist’s recurring gripe about hanging around while his “two hundred thousand dollars’ worth of machinery is ticking over out there” was originally the then princely sum of $10,000. But the play’s innate strength – of observation, motivation and character – doesn’t need updates. These people are only too familiar. There are ripples of laughter throughout the audience, but it’s probably recognition rather than straight up amusement; mostly the unfolding satire and drama is viewed in absorbed silence.

As you may have read elsewhere, Danny Adcock stepped in at late notice to replace Steve Bisley; and the media was asked to give the cast a few more performances to allow them all to settle. On Monday evening (February 9) it wasn’t obvious that Adcock was the new cop on the block. His performance is vilely authentic as a man who can boast to the raw recruit of a long and successful career of studied laziness and corruption. He is simultaneously funny and horrifying.

Two actors new to STC make terrific and welcome debuts with the company. As the boofhead hubby Kenny Ashley Lyons manages the balancing act between brutish charm and innocent incomprehension (“it was only a love tap”) and takes the audience on an interesting journey from repulsion to pity because, in retrospect, Kenny is Constable Ross’s doppelganger. As the weak-kneed constable, Dale March makes Kenny’s journey in reverse. His good intentions and aspirations have shallow roots and the nice young man is revealed to have a handy pair of fists when goaded far enough. His sense of self preservation is also strong, if a little loosely wrapped, and March manages the transitions with ease.

The two sisters are more problematic and it may be something to do with the casting. Or may not. As elder sister Kate, Sacha Horler instantly makes you wonder why she isn’t cast more often in rewarding roles of depth and subtle humour. What she can do with one sexy eyebrow is worth a masterclass in itself. She’s a joy to watch even though Kate is a mean, social-climbing bitch.

It doesn’t seem likely, however, that she and little sister Fiona (Eve Morey) emerged from the same womb via the same parents. Fiona is a pale and peripheral figure most of the time and it’s hard to see her as the (albeit unwitting) catalyst for what happens in the play. Alan Flower too, seems uneasy as the removalist who just wants to get it over and done with and get on to the next job. It’s as if both characters have been accidentally put through a bleach wash and their colour removed, and the whole rendered uneven.

Nevertheless, it’s likely that the cast will settle into a more assured rhythm as the run progresses and anyway, the play is the thing. As it is, director Wayne Blair leaves it alone and orchestrates the physicality of the piece with an eye for the always tricky Wharf space and the curious blank white raised dais that doubles as the Carter unit and the police station (design Jacob Nash and lighting Luis Pampolha).

All in all, it’s fascinating to see how accurate Williamson was and is in his portrait of authoritarian Australia where “she’ll be right” and the carefree larrikin are as mythical as the bunyip.