Address Unknown

Address Unknown Moira Blumenthal Productions Downstairs at the Seymour Centre; October 14-November 7, 2009

Kathrine Kressmann Taylor or Kressman Taylor as she was known in the 1930s and 40s when a playwright with a female name was apparently deemed unlikely to be taken seriously – hello Currer, Acton and Ellis – is possibly as interesting as her 1938 novel from which this one act play is adapted. Not that you’d know that from the program accompanying this production which says nothing about her but carries two pages of material by and about the director/producer. If you’d like to know more about Kressman Taylor and the remarkable history of her novel and play – and her equally remarkable life and career – then go to Wikipedia, where you’ll discover quite a lot.

In brief, Address Unknown was written and published in the US in 1938 and, according to Wikipedia, “is credited with exposing, early on, the dangers of Nazism to the American public.” It was filmed by Columbia Pictures in 1944, republished by Reader’s Digest and banned in Nazi Germany. Again, according to Wikipedia, “In 1995, when Kathrine was 91, Story Press reissued Address Unknown to mark the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the concentration camps. The novel was subsequently translated into 20 languages, and the French version alone sold 600,000 copies. The book finally appeared in Germany in 2001, and was reissued in Britain in 2002. In Israel, the Hebrew edition was a bestseller and was adapted for the stage. The stage play has since begun a whole new life of its own and the book and play have been experienced by hundreds of thousands of people.

During her 50 years of comfortable obscurity, Kathrine Taylor married, was widowed and married again and for most of her life commuted at six monthly intervals between Minneapolis and Italy with her sculptor second husband. Then, after the reissue of the book, she “spent a happy year signing copies and giving interviews until her death in July 1996 at age 93.”

Knowing something about Kathrine Taylor puts into perspective the stage adaptation of the novel, which is epistolary in form – a notoriously difficult thing to make work on stage. This adaptation is by Frank Dunlop and pretty much succeeds in overcoming the static and essentially undramatic structure of letters between two people who never meet but, for the sake of the audience, must communicate and interact. (84 Charing Cross Road and You’ve Got Mail are other examples of the visual and dramatic obstacles of letters as protagonists.)

Martin Schulse (Patrick Dickson) is an art dealer who returns to Germany from the USA to take advantage of the new Nationalist policy of outlawing “degenerate art”. It is 1933. His partner in a gallery in San Francisco is Max Eisenstein (John O'Hare) a German Jew; the two have been close friends for many years – practically brothers – and share an affection untouched even by Martin’s passionate extra-marital affair with Max’s younger sister, Griselle.

Over the course of a series of letters sent back and forth during the year, the events unfolding in Germany – the new leader emerging, German pride being restored, the sinister shift in attitude towards “your race” as Martin writes to his fellow German – are gradually teased out. It’s nicely done by the writer inasmuch as almost none of us realise the significance of world events until later and most of us are preoccupied by tiny matters that directly affect us. For Martin and Max, their interests initially, are in finding and selling paintings to their mainly rich American Jewish clientele. Innocent enough, but gradually the tone changes.

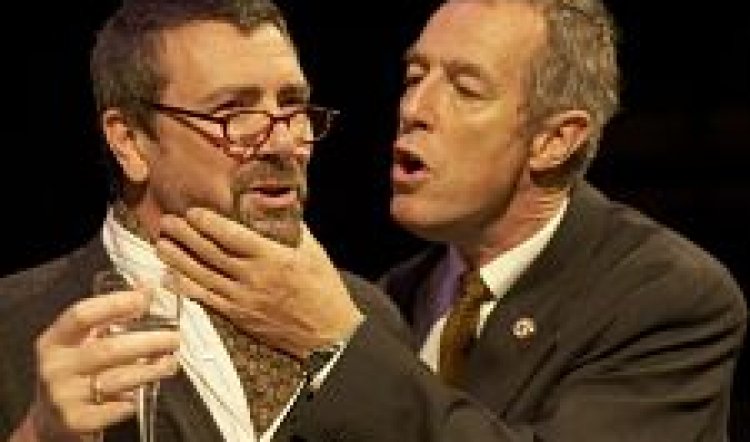

At first Dickson and O’Hare occupy their own studies, one in America, the other in Germany. (An atmospheric and well-realised set designed by Barry French). Over the course of the play they stray into the territory of the other – Max’s all modernist glass and chrome, Martin’s baronial and Bavarian, but of course never meet in person. The incursions occur as Martin’s increasing involvement with Nazism begins to permeate his mind and attitudes. It’s chilling to witness the infection of Hitler worship spreading through the person of one previously liberal, intelligent man and the growing distance between the two even as they are physically at their closest on stage.

Dickson and O’Hare are fine actors and maintain a delicate balance in bringing life to the “letters” without recourse to the temptations of melodrama or the equally deadly opposite: defeated talking heads. It’s an accomplished duet by both and they maintain tension and attention for the play’s 90 minutes.

The denouement is particularly satisfying for anyone who has ever wished that “revenge is a dish best eaten cold” weren’t the socially acceptable norm. In this instance revenge is total and terrible, but in the circumstances, awfully satisfying. It would be interesting, however, to know what happened next. The play ends in early 1934, Kristallnacht was still five years in the future – and the year Taylor’s book was published. But one has to imagine the playwright felt she had done what she set out to do: warn of the growing threat of Nazism and Hitler. And it now resonates, in its small yet powerful way, for another generation.