THE HISTRIONIC

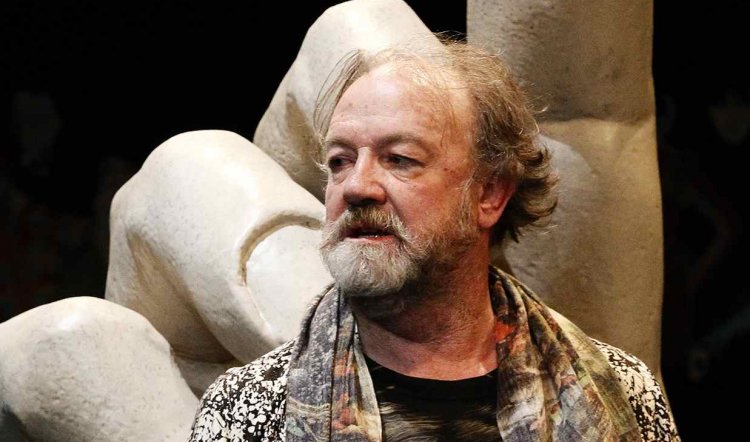

THE HISTRIONIC, Sydney Theatre Company and Malthouse Melbourne at Wharf 1; 20 June 2012. Photos by Jeff Busby, main: Bille Brown and Barry Otto; right: Bille Brown.

This play, by the late Thomas Bernhard, translated by Tom Wright, and featuring the much admired Bille Brown, arrives in Sydney from Melbourne high on the "much anticipated" list. As a play it's another German (language - Bernhard was Austrian) curiosity that follows the STC's Gross und Klein by Botho Strauss. "Curiosity" in that each of these plays is structured around one huge central performance supported by a company of fine but extremely subsidiary actors. However, where Cate Blanchett's wondrous turn as Lotte Kotta was all subtleties and a mesmerising disappearing act, Brown's egomaniacal actor-manager Bruscon is an overwhelmingly monstrous creature.

According to director Daniel Schlusser, The Histrionic (Der Theatermacher) is the playwright's revenge on Salzburg. When Bernhard's play The Ignoramus and the Madman premiered at the city's festival in 1982, the local fire department disallowed a moment of total blackout by insisting the emergency exit lights stay on. Two years later, The Histrionic was staged in Salzburg and the city's great and good found themselves satirised as the inhabitants of rural Utzbach, population 280, where the arrival of the great Bruscon and his hapless family company coincides with the weekly Tuesday excitement of Blood Sausage Day. As Bruscon quickly discovers, the place stinks of pigs, the people are stupid and Hitler's portrait still hangs in the village hall. And they also have problems with turning off exit lights.

Austria - and yes, this is a generalisation - doesn't have much of a reputation for humour or self-irony, so it can only be imagined with delight just how the audience felt about Bernhard's spray at its expense. Bernhard has been likened elsewhere to Patrick White, the curmudgeon whose disdain for his country's bourgeois pettiness and klutzy nationalism often obscured the depth of humanity that resides in his plays. But where Australia's worst crime, aside from ancestral theft, was seen by its great playwright as its lack of culture, Austria's villainy, according to Bernhard, is its over-arching pride in its culture and consequent superiority. It has meant, on the one hand, Mozart and Haydn. On the other, apfelstrudel, Arnold Schwarzenegger and an abiding sense that Nazism and Adolf Hitler weren't such a bad idea.

Nevertheless, the character of Bruscon - a pompous, self-satisfied bully and an absurd but all too realistic excrescence of a man - is a difficult one on which to hang 100 minutes of non-stop bile and contempt. In the most predictable way, the role must be considered a gift to an actor, particularly one of Bille Brown's power and wit. Being careful what one wishes for, however, is possibly not the first thought that comes to mind when being offered such a gift. As it is, Brown's greatest success with the role - laying bare Bruscon's superficiality as an actor and ghastliness as a human being - becomes the ultimate failure of the play or the reading of the character (hard to say which).

And that's where this story started (see first paragraph) with the idea of subtlety. In the cast of seven, that also includes Jennifer Vuletic, Kelly Butler, Josh Price, Katherine Tonkin and Edwina Wren, is Barry Otto as Utzbach's landlord. It falls to him to put up Bruscon and his family and also to put up with him. The play requires that the landlord, like the others, should say very little but contribute much. And Otto's characterisation of this pathetic man is one of the best things he's done in years. The landlord is a nervous, wretched wreck of nothingness; knock-kneed, lank-haired and desperate to please while simultaneously trying to disappear into the woodwork and keep out of trouble. Casting Otto as Bruscon, however, might have given that character the pathos, light and shade that Brown's spectacular yet more one-dimensional playing does not.

At the same time, it's often wildly funny as a series of classic theatre jokes and Brown milks the moments of hamminess for all they're worth. That we never get to see Bruscon's allegedly fabled play The Wheel of History (in which he realises his narcissistic dream of assembling similar leviathans such as Einstein, Churchill, Napoleon, Metternich and Hitler) is a small blessing.

Within the real production, light and shade and some respite from Bruscon's tyranny is rendered by the other actors. Jennifer Vuletic is a hilariously malevolent presence as his oxygen-snorting, asthmatic wife. Their two children and apparently hopeless actors, Edwina Wren and Josh Price, choreograph their existence around him, almost indistinguishable from the discarded and absurd props and detritus from previous shows that litter the bedraggled theatre. (Design and lighting by Marg Howell and Paul Jackson.) The landlord's wife (Kelly Butler) is an oasis of cleavage and relative normalcy and a counterweight to the glaucomic, caliper-wearing Erna, a wraith of a girl who probably exists in any community where making sausages is the social highlight of the week.

Not in the cast but somewhere in the ether: solid citizen Josef Fritzl who could have been a typical citizen of Utzbach. His grim face kept popping into my mind during Bruscon's relentless spit of contempt, intimidation and emotional dishonesty. Fritzl is just three years younger than Bernhard and was born in Amstetten, a small town only 170 km from Salzburg. Rather than railing at small town pettiness over a couple of lights, it would have been transfixing to see how Bernhard's deep-seated fury at his homeland's capacity for awfulness might have been directed - if the discovery of Fritzl's atrocities had been revealed before Bernhard's death in 1989.

In fictional Utzbach, nobody thinks it's odd or not quite right that Hitler's picture still hangs in the village hall. In greater Austria, nobody thought it odd or not quite right that a wartime Nazi, Kurt Waldheim, became its president after being Secretary General of the UN. And nobody in Amstetten thought it odd or not quite right that the Fritzls' daughter disappeared (actually imprisoned in the basement of the family home); that babies then appeared on their doorstep at intervals until they had three children. And the local law failed to find out that Fritzl was a convicted serial rapist before going on to sexually abuse his 11-year-old daughter over 24 years and father seven children on her. In what Bernhard would surely have turned into the blackest satire, Fritzl blamed it all on growing up in the Nazi era, with its alleged emphasis on decency and discipline; and on his (single) mother whose treatment of him left him humiliated and weak! If it weren't so vile it would be funny - Bernhard would surely have thought so.

As it is, however, 100 minutes of bluster and haranguing of the citizenry of Utzbach over the recalcitrance of a petty bureaucrat felt like 40 minutes too many. Possibly the only good thing about being repeatedly hit over the head with a mallet is the moment when it stops. But the play and its underlying themes are provocative and could be illuminating. I was amused, appalled and eventually bored, but a lot of thinking and wondering went on.