DIDO AND AENEAS

DIDO AND AENEAS, Sasha Waltz and Guests for the Sydney Festival at the Lyric Theatre, The Star. 16,17,19,20 and 21 January 2014. Photography by Jamie Williams.

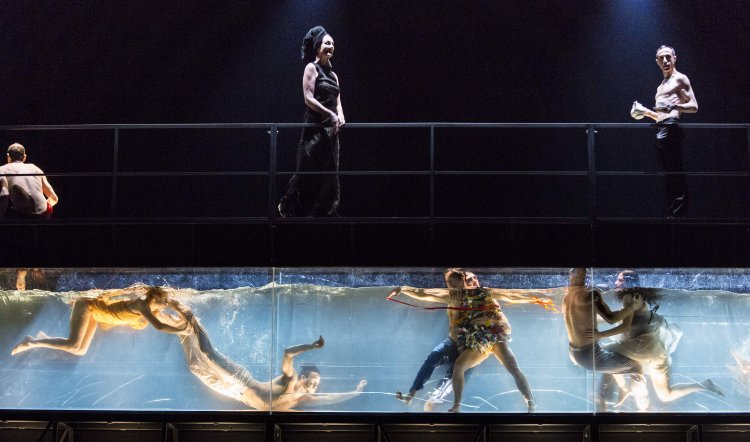

Unless you've been asleep for the past few weeks you will know a very large and dreamily lit fish-style tank containing 7.5 tonnes of water is the key image of the centrepiece production in the 2014 Sydney Festival. Suspended in a scaffolding frame on wheels with a walkway above it, the tank dominates the cavernous stage of the Lyric for the opening sequence of German choreographer Sasha Waltz's some-swimming, all-dancing, bit-of-singing version of Henry Purcell's opera of the late 1680s.

The tank takes the place of the opera's lost prologue - which happened underwater - and is the picturesque setting for some of the dancers to swim and cavort in the opening sequence. Meanwhile Attilio Cremonesi's musical reconstruction is directed by Christopher Moulds with the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin to set the musical tone and are a reminder that we are actually in the presence of a Baroque opera.

Ten-plus years ago this Dido and Aeneas may have been a bit bold and original, now it seems dated and perhaps more a result of Berlin's habit of throwing big budgets at artists than actual creative thinking. The tank is the first and costliest symbol of that possibility and it's difficult not to see it as a gimmick in search of purpose. Yes, there are some lovely images as performers do graceful things in it, but where was the basic and vital question "And then what?" - which should be asked of any bright idea - before it's found to have insurmountable problems bobbing in its wake. In this case, the question would have highlighted the severe distractions that follow.

After the prettily lit grace of the underwater sequence (lighting Thilo Reuther) the performers climb out of the tank and awkwardly drag off their sodden clothing (trousers or shifts depending on gender) and equally awkwardly drag on fresh costumes over wet skin. If any in the audience are able maintain contact with the text and music while all this is going on, they have better powers of concentration and interest than I.

The same applies to a device used twice during the production - when two dancers are hooked up to wires suspended at either end of a horizontal bar. It's lowered from on high and enables them to counter-balance each other and leap about and twirl in aimless circles upstage right while, in one instance, Aeneas (Reuben Willcox) struggles to attract our attention downstage left.

Trouble is, there is something seriously awry with a show that requires an extensive explanatory program interview with the auteur plus the libretto - handily left on each seat - for it to make sense. Even then, there are so many diversions and bits of business thrown into the mix that you'd be hard pressed to follow the action, previously familiar with it or not.

As it is, it's hard not to suspect that Waltz had little faith in the opera itself to devise so much extraneous colour and movement for her audience. Dame Edna would approve of that at least - it has long been her method of dealing with restless tinted folk. Not that there were many in the audience on opening night, nevertheless restlessness quickly broke out and a few dozen left before too long.

As it happens, these were probably people who came to see an opera whereas this Dido and Aeneas is largely about dance. Each of the principals is represented by both a dancer and singer which makes for some intriguing cross-pollination of representation. As Waltz is a choreographer, however, it's perhaps inevitable that dance should dominate over the singers. This is partially unintentional: first of all, there's the positioning of the splendid Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin just below the stage, rather than in a pit modern style, and therefore at ear level with the stalls. It means even the soft tones of period instruments easily obscure the voices.

Secondly, the Lyric's stage is deep and tall and some of the voices are relatively small - audibility is a problem, as is clarity in the absence of surtitles and the presence of some non-English speakers. And if that's not enough, the dancers are many and the thumping and bumping of feet is like feeding time in the elephant house.

The mood in the auditorium palpably changed when halfway through an interminable dance interlude - that resembled rehearsal room exercises without music - a momentary interruption came from a despairing voice. "What has this to do with the opera? Please tell me!" He called. People relaxed after that, secure in feeling bewildered and irritated rather than stupid and patronised by a superior intellect.

Mezzo soprano Aurore Ugolin (Dido) and Deborah York (Belinda) have the best of it vocally, together with the ensemble Vocalconsort Berlin. Ugolin was even permitted to deliver the famously beautiful Dido's Lament without choreographed distraction, but by then - for me anyway - it was too little too late. Bored to sobs.