THE LONG WAY HOME

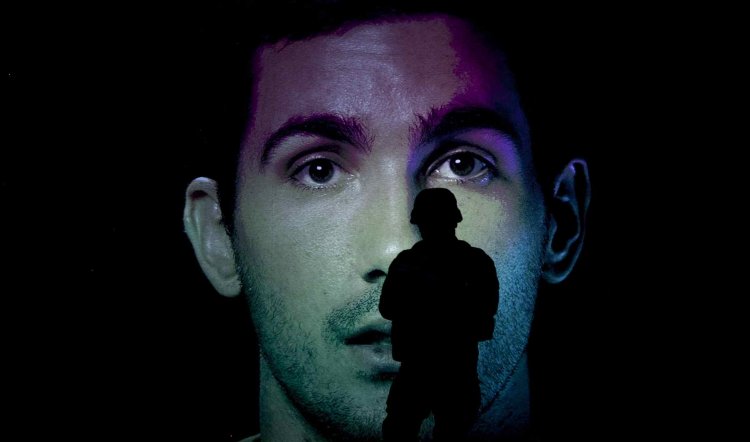

THE LONG WAY HOME, Sydney Theatre Company and the Australian Defence Force at the Sydney Theatre, 7-15 February 2014, then national tour. Photography by Lisa Tomasetti: Tim Loch, Odile Le Clezio, Craig Hancock and Emma Jackson (above); Will Bailey (right).

This unique army-theatre collaboration has been much-anticipated since it was announced, late last year, for the STC's 2014 season. At that point it was little more than a dramatic image - of silhouetted soldiers in a bleak desert landscape - and the name of the playwright - Daniel Keene. In the past few weeks it has also been much-publicised and talked about in the run-up to opening night and no wonder, the idea is electrifying.

It's genesis was a night out at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket for the Chief of the ADF, General David Hurley. There he saw The Two Worlds of Charlie F, a play which dramatised the combat and post-combat experiences of a group of British veterans of but the latest Afghan war. Hurley's immediate response was that something similar should happen in Australia. Happily for us, his point of contact in civvy-land was Sydney Theatre Company's Andrew Upton and the project was underway...

Upton sought out Stephen Rayne, the UK creator-director of Charlie F, and he brought with him to Sydney his invaluable experience of getting veterans to trust and to talk and eventually to loose the dogs of their nightmares. He and Keene spent weeks with a wide range of vet-volunteers and from that listening and questioning process the playwright then fashioned characters for the eventual company of professional actors and "amateur" veterans.

The decision not to take the more obvious verbatim theatre line proves crucial to the experience, both for participants and audience. According to Keene, after getting over the initial surprise, the vets embraced the idea of being someone else; not least because the essential personal truth and integrity of the stories are untouched. And as any actor knows, it's much easier to be a character than to bare your own fragile self on a stage.

Consequently, what is revealed in the deep, dark cavern of the Sydney Theatre is a world beyond the imagination of ordinary people. And therein lies the first irony, because that world is one in which ordinary people volunteer to spend weeks, months, even years of their lives. And it's one from which they know they may not return and if they do, they will never be the same ordinary person in an ordinary life ever again.

In his director's program notes Stephen Rayne writes, "The regiment of the wounded is the largest and fastest growing in the world today and, with the drawdown from Afghanistan happening later this year, this regiment will only continue to grow." What he doesn't say, but which you'd have to be blind and deaf to have missed, is that the consequences for that regiment and the wider society to which it returns is - in more and more instances - catastrophic.

The play opens with familiar war motifs - crashing rock chords, explosions, unintelligible voices and blinding flashes (composer and sound designer: Steve Francis). It's disturbing in its reassuring familiarity and it's not long before we're confronted by one of many sardonically humorous insights: one soldier tells of watching The Hurt Locker, then Googling the movie's military adviser and "trolling the fuck out of that fucker". Okay, so war is hell and although we glibly nod and say we know that - we know nothing.

Renee Mulder has devised an ingenious and effective set - ready to tour the country - consisting of a large back screen on which a series of projections (Mulder and David Bergman) tell us, Brecht-style what's about to happen or where we are. Lighting (Damien Cooper) does the rest - the first image is the now iconic one of silhouetted soldiers in full robot-like battle camouflage walking across a shimmering mirage of desert. But these are for real and they - our boys - hang about like a silent chorus of witnesses in various configurations for the rest of the proceedings. They are ghosts, or the illusive companions of never-ending PTSD nights for those who've "returned".

Humour is a large part of the two hours and ten minutes (including an interval) of The Long Way Home. It has to be - the power of the accounts and anecdotes are such that without laughter, they would be unbearable. One young private - on sentry duty at the god-forsaken end of the night in a god-forsaken corner of dusty desert - tries to stop talking to himself, but keeps replying anyway. "It's that STD thing," he tells himself. "Yeah…"

Is he crazy or going crazy? Yes and no: he's lonely and afraid; he's been lonely and afraid for months and still he dutifully does his job. That's what's crazy. The flares of insight that illuminate this dark place reveal much that is deeply discomfiting about the army, its methods and its reasoning. More discomfiting is that it's presented with such drollness in all its absurdity to a civilian audience that, to that moment, can have had no idea what goes on in its name and on its behalf.

Daniel Keene has observed, "Their wounds are not always visible and their memories may remain unspoken. But we expect them to forget, we expect them to be healed. Or perhaps that is only our profound wish. The reality is different. The reality is more difficult." This seems particularly true of the most recent conflict - Afghanistan - in which Australians have been embroiled. Why should this be so? Aussies have gone to war for righteous and not-so-righteous reasons since the Boer War called on us to help the Mother Country. Men (and they were men until recently) came home "shell shocked" or maimed and basically got on with it, or not. But there is something different about the modern wars and its effects on survivors, visibly wounded or otherwise. Again, why should this be so?

Lying semi-comatose in a hospital bed for much of the play,a young man (Gary Wilson) struggles to communicate something to those who come to or pass by his bed believing him unable to speak or hear. Fragments of what he says are cast on the back wall and, like his jumbled but ultimately meaningful thoughts, they eventually make sense:

"…Many were they whose cities he saw, whose minds he learned of, many the pains he suffered in his spirit on the wide sea, struggling for his own life and the homecoming of his companions. Even so, he could not save his companions, hard though he strove to…"

It's from the opening lines of The Odyssey and Homer could be describing the worst symptoms of PTSD - post-traumatic stress disorder. Sufferers may be traumatised by what's happened to them, by what they've seen and done, but - now commonly recognised - what is more likely to haunt and kill is the guilt they feel as survivors, as those who failed to save a comrade, those who did come home, as those who have no firm grasp on what and why - the basic morality of the war in which they found themselves.

These symptoms and the reasoning would be all too familiar to Vietnam veterans - the other Australians who were sent to an unjustifiable and unjust war. And for those who've served in Afghanistan, they now have the bitter and unfathomable experience of watching the Western governments that sent them to get rid of the Taliban conceding the country back to these same men, with bonuses. What was it all about? What was it for?

Those questions are not raised in this play - that's something for another time and true crime fiction or more likely, black farce. What we do learn or are reminded of, however, is the extraordinary nature of the ordinary and the dreadful nature of modern warfare - which appears to be as much psychological as physical because of the range of technologies that aid and abet it in every direction.

The actor-soldiers are mainly tremendous - the invisibly damaged good blokes whose wives are clearly in danger (Craig Hancock and Tim Loch) are at once touching and menacing. Emma Jackson and Odile Le Clezio are the actors who powerfully represent those wives, while Iraq survivor Sarah Webster (whose character imparts a painful truth: the worst of being wounded is the boredom) and Afghan vet Emma Palmer whose good ol' boy-girl character is an eyebrow-raiser in a milieu that is infamous for its intolerance of women or minorities are the other women on stage in the company of 17. It will be fascinating to check back at the end of the tour to see how it all pans out. It could be a whole other play…someone must keep a journal!

The structure of the multiple narratives is a relatively simple arc, which is as well because the complexity of the stories and the hell of where and how they're told is dizzying. The vets take on numerous cameo and larger roles and are Will Bailey, David Cantley, James Duncan, Wayne Goodman, Kyle Harris, Patrick Hayes, James Whitney and Gary Wilson. Actors Warwick Young, Martin Harper and Tahki Saul complete the boys' company and it's the two cameo scenes performed by the latter that make for the only seriously awry moments in the show. It's no fault of the actor - who performs the comic character of an officer who goes along to CWA and RSL gatherings to explain the army - but in the program, during the performance, I scribbled "dump Neville Stiffy". This silly cameo and the not-very-funny schtick sticks out like dog's balls and could as easily be snipped out. Lt. Neville Stiffy (geddit? geddit?) is a jarring falsehood in an otherwise profoundly honest and candid play.

The Long Way Home is demanding, fascinating, rich and raw. Coming in so close to Black Diggers there are bound to be comparisons, but they should be avoided - each is what it is and both are different yet complementary. Both plays tell us, forcefully, that we need to take a long hard look at ourselves and our myths and legends. Waving flags on Anzac Day or placards at anti-war demos just doesn't cut it as a rational, adult response to what happens in our name - and to whom it happens.

The Long Way Home is the first - and long overdue - step in illuminating publicly what lies ahead for those who've served and suffered on our behalf - and the families who've suffered and are suffering alongside them. See it, and be prepared for the constant poetic pounding of the "f" word!