A Disappearing Number

A Disappearing Number, Complicite presented by STC, Sydney Opera House Adventures and the British Council; Sydney Theatre at Walsh Bay, 19 November-December 2; phone: (612) 9250 1777

Propinquities abound in A Disappearing Number, the latest show from unexpected and welcome visitor, the UK’s mind-bending company Complicite. Having not been here for more than a decade, an unscheduled hole in the international touring plan was leapt upon by an enterprising new combination of the Sydney Theatre Company, Sydney Opera House and the British Council – and here they are for a couple of precious weeks.

In addition, kinship is to be found in Complicite’s history (more a state of mind than a theatre company) and the mixture of constancy and fluidity since its genesis in 1983 (as Theatre du Complicite). Simon McBurney is the common thread from then to now and reinforces the mathematical idea of infinity being achievable by counting forward or backward from one! Or, put it another way, the present and the past are always with us either in actuality, memory or imagination.

Essentially that’s what A Disappearing Number is about and although on one level it is “a show about mathematics”, those mathematical illiterates among us shouldn’t be put off. Math is a series of puzzles and patterns and the work is really about the similar puzzles, patterns, close links and threads to be found in stories, life and love – which a proper mathematician might say is what sums are all about anyway.

A Disappearing Number collected the Laurence Olivier Award 2008 for Best New Play, the Evening Standard Award 2007 for Best Play and Critics' Circle Theatre Award 2007 for Best New Play and within minutes of curtain-up it’s apparent why. It’s the kind of unexpected, unpredictable, bold, cerebral, funny, clever, simple, intensely felt and dazzling theatre that’s long been associated with Complicite.

There are a number of pasts and presents woven into the narratives, aside from concepts of infinity (which is the past and present, depending which way you’re facing) and the most instantly striking, from an Australian perspective, is probably the way the Empire has struck back yet again. Once upon a time the Indian sub-continent’s presence was felt in Britain mostly in economic terms as its merchants and adventurers piggy-backed on military might to siphon India’s resources into the royal coffers. For a couple of centuries, England mercilessly exploited India and its peoples to the best of its considerable ability. This is illustrated in elegant style by bestsellers such as The Raj Quartet, A Passage To India, The Far Pavilions, Heat and Dust and The Jewel in the Crown.

On a visit to London, Mahatma Gandhi once was famously asked what he thought of British civilisation and replied, “It would be a very good idea.” And so it remained, pretty much, until 1947 and independence – a moment to be recalled later by the first prominent brown person to reverse the cultural flow – Salman Rushdie with Midnight’s Children. (Although born in Bombay, he was typical of the Indian-Anglo intellectual upper crust in his Rugby and Cambridge background.)

Then, in the 60s and 70s, a generation of poor immigrants from mainly India, Bengal and Pakistan and other former British colonies began arriving. They settled into the traditional immigrant area of east London’s Hackney and Bethnal Green, centred on Brick Lane, and a unique community and culture formed and spread to the Midlands and the north. The next generation has gone well beyond the East End’s butter chicken ghetto, whether or not its origin was there, or other parts of the disintegrated Empire. Names such as Hanif Kureishi, Akram Khan, Nitin Sawhney, Gurinder Chadha and Monica Ali have become influential in British culture. As has the English language work of Rohinton Mistry, Arundhati Roy, Vikram Seth, Bharati Mukherjee and so on.

For Australians, whose experience of the Sub-Continent is mainly cricket and Shane Warne’s well known loathing of the food, the trickle of English-Indian artists over the past few years has been eye-popping. Novels are one thing, breathtakingly talented, living breathing artists (such as Akram Khan) are another: they’re in your face and have to be dealt with in quite a different way. The same might be said of the central character in A Disappearing Number.

Srinivasa Ramanujan was born in 1887 in the small town of Kumbakonam, beside the Cauvery River, about 270 kms from Chennai (then Madras). He was a Brahmin but the family was not well off, his father was a clerk. Ramanujan did not do well at school and could not go to university, even if the family could have found the funds to send him. Nevertheless, early on he developed a passion for mathematics.

In 1913, out of the blue, fabled Cambridge mathematician G.H. Hardy received a letter from India. It was from Ramanujan who was then an accounts clerk at the Madras Port Trust. The young man politely introduced himself, confessed to being ill-educated then presented for Hardy’s approval sheafs of paper covered in formulae and theorems. Not surprisingly, Hardy thought he’d been targeted by yet another nutter.

Later, however, something about the work caused Hardy to return to the letter and, despite its unorthodox style, he began to study the work. According to his own recollection, he realised the author was a unique talent, a mathematical genius. Despite the consternation of colleagues, Hardy invited Ramanujan to Cambridge where they worked together to produce some of the most important advances of the 20th century.

Ramanujan’s approach to maths is encapsulated in a story from his childhood when a teacher is trying to get his class to understand the simple arithmetic by way of visual images. The class was instructed that if you subtract three goats from five oranges you will have to oranges. Ramanujan found that absurd. Similarly, when told that 43 fishes could be given to 43 girls so that each would have one. He asked, “Do all numbers go into themselves once?”

When the teacher agreed, Ramanujan extrapolated that if he had no children to give no fishes, the answer would be One. Because, he reasoned, zero is a number, it is not nothing! History does not record what the teacher made of this leap of logic and imagination.

A Disappearing Number is full of these and other such leaps of logic and imagination. Simultaneously it tells the story of Hardy (David Annen) and Ramanujan (Shane Shambhu) in the early years of the 20th century as well as that of 21st century mathematician and lecturer Ruth Minnen (Saskia Reeves) who goes from England to India in search of Ramanujan’s notebooks. Ruth meets Al Cooper (Firdous Bamji) a US-born futures trader of Indian ancestry who falls for her, and eventually, she for him. But their relationship is as fractured and unsatisfactory as an unproven theorem as they pass and re-pass one another in the global criss-crossing of modern, mobile phone-led work practices.

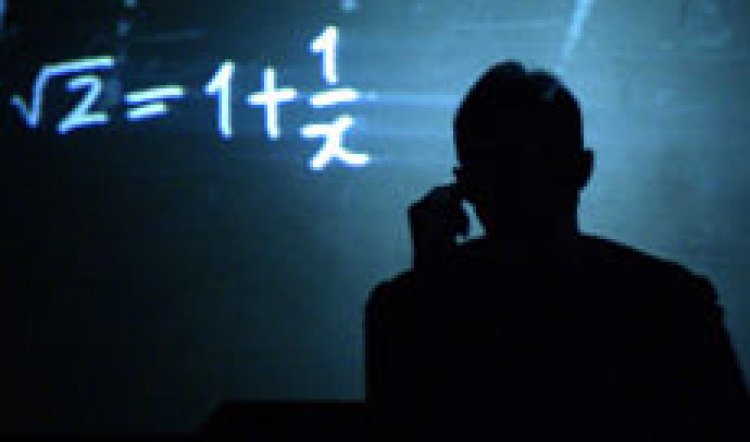

The horizontal figure of eight that signifies infinity is central to the narratives and the movement on stage as characters don’t quite intercept across time and space and desire. The deceptively simple white set of flats and screens are choreographed as intricately as the actors in movements, projections and lighting that take the action from whiteboards in lecture halls to the bustling streets of Chennai and the serenity of pre-WW1 Cambridge.

The final propinquity – death – is illustrated with touching and at the same time droll clarity by the predominance of the mobile phone: Al’s most consistent relationship throughout the piece is with the disembodied voice of “Barbara Jones” a call centre worker who is trying, in a heavy Indian accent, to sell him a new number and package. At the same time, Ruth is in far-off India on the trail of the long dead young man without whose work there would be no technology for a mobile phone.

As she travels further from the regimented thinking of her rarified education she inexorably comes closer to what is, for her, the frightening concept of Ramanujan’s ill-educated use of intuition and imagination. As she realises that it produced the work she worships, she also realises that what has happened to her with Al is also about similar human responses.

A Disappearing Number is a droll title for concepts and stories that re-appear and re-form just as each seems on the point of vanishing. The whole is a series of ravishing ideas and images that you can choose to simply surf or dive deep into. The conceit, wit and daring of the piece and the confidence of the actors in what they are doing are thrilling. Funnily enough it sags somewhat in the middle, weighed down by a bit too much math perhaps, but even that gives you a chance to consider the moment and go off on your own flight of fancy. Then, in the twinkling of a pi it picks up again and rips right up into the stratosphere.

A Disappearing Number is an amazing, exhilarating experience that made me feel happy, touched, humble and smarter, all at once.

Conceived and directed by Simon McBurney, devised by the Company; original music Nitin Sawhney; design Michael Levine; lighting Paul Anderson; sound Christopher Shutt; projection Sven Ortel for mesmer; costumes Christina Cunningham. Performed by David Annen, Firdous Bamji, Paul Bhattacharjee, Hiren Chate, Divya Kasturi, Chetna Pandya, Saskia Reeves and Shane Shambhu