A LIFE IN THE THEATRE

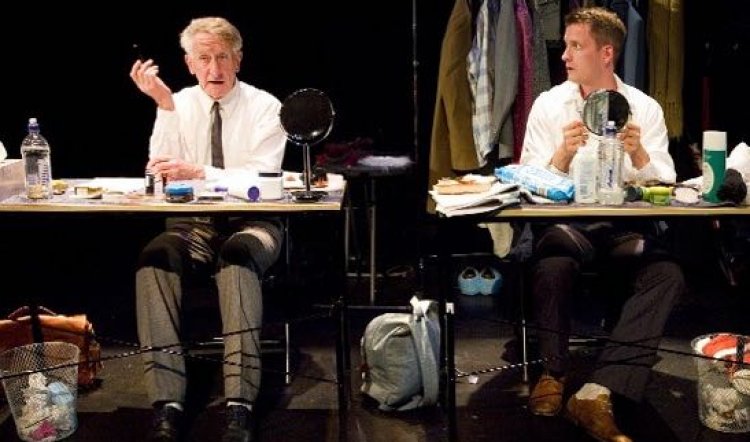

A LIFE IN THE THEATRE, Eternity Playhouse, 8 November-4 December 2016. Photography by Helen White - above Akos Armont and John Gaden; below - John Gaden and Akos Armont

In 26 quicksilver scenes involving almost that many on-stage costume changes, veteran actor Robert (John Gaden) and younger, greener John (Akos Armont) make a sparkling yet comically seedy portrait of theatre life.

The Eternity stage is tricked out as the unglamorous yet always fascinating backstage and dressing-room areas of a theatre whose auditorium is the balefully dark and intermittently lamp-lit upstage (set Hugh O’Connor, lighting Christopher Page). And this 80-minute David Mamet classic from 1977 is orchestrated with wit, insight and hilarious precision by director Helen Dallimore and the result is both funny and melancholy by turn.

In A Life in the Theatre, Robert has, quite frankly, seen better days but is not yet willing to give up his own pre-eminence. He benevolently advises and lectures John in ways guaranteed to undermine the young actor. At first John listens attentively and is regularly unnerved or deflated by his kindly colleague.

The “life” and “theatre” they give us includes vignettes and pastiches ennui-drenched Chekhov to something like All Farcical on the Western Front, through teddibly teddibly Cowardesque drawing room drama all delivered with the utmost seriousness and awfulness that only very fine actors could pull off.

The play is a mix of high comedy, low farce and actor-skewering satire all delivered with deliciously knowing elan. But...there is an underlying desolation that slowly grows as the trajectories of Robert’s and John’s lives meet and pass, one on the way up, the other on the way down.

John Gaden’s Robert is a pompous fellow whose barely hidden loneliness is no less painful for being self-inflicted. His aggressive garrulousness would be all too familiar to many in any kind of workplace, or home, and the urge to whack him is strong for John and audience alike. Yet he shrinks before our eyes as Akos Armont’s John equally visibly grows.

All this action takes place to a fabulous woodwinds soundtrack (Jed Silver) during a season of ramshackle repertory theatre. It is the kind of enterprise, along with summer stock, that was virtually dead when Mamet wrote the piece. It’s sketched in via tiny moments – John has to borrow twenty bucks from Robert for dinner, Robert goes home alone to a small apartment, their costumes are unwashed – and these details drift back into the mind afterwards.

And that’s the curious thing: this seemingly slight confection carries more weight and humanity than is at first apparent. It’s partly the casting of two of our best actors and partly the director’s ease with the world and the work. Although it’s rather ridiculous, it’s also true and lovingly understood. A funny sort of magic, but magic nevertheless. Recommended.

(NB: to get a deeper, darker feel for the American theatre world inhabited by John and Robert, read Tell Me How Long The Train’s Been Gone by James Baldwin.)