A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE

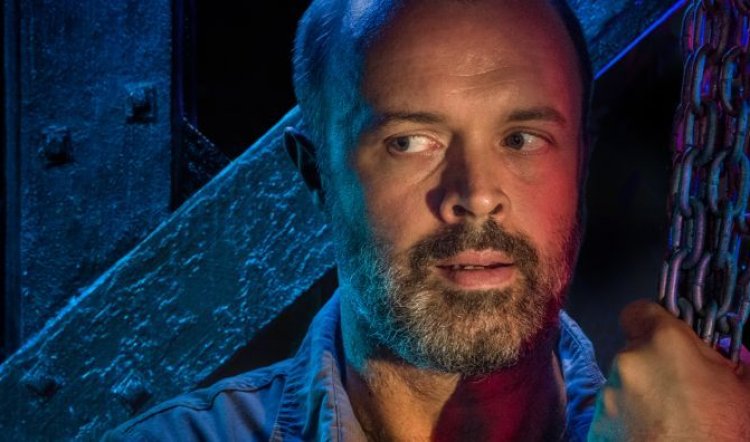

A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE, Redline Productions at Glen Street Theatre, 30 January-4 February 2018. Photography: above Anthony Gooley; below - from the Old Fitz production

Master director Iain Sinclair’s A View From The Bridge, was Red Line’s most lauded production and biggest box office success of 2017. The Old Fitz run (18 October-25 November) quickly sold out and the announcement of a season at Glen Street early in 2018 marked an exciting new initiative for both companies. Then the show picked up Best Independent Production, Best Actor (Ivan Donato) and Best Supporting Actor/co-Best Newcomer (Zoe Terakes) in the Sydney Theatre Awards.

In the interim, the staging has been re-rehearsed, redesigned and re-lit to move it from the taut intimacy of the Old Fitz’s 60-seat black box to the 400-seat conventional theatre space of Glen Street. Its director could be present only briefly and Andrew Henry stepped into the directorial breach. As if that were not enough to cause frightmares, Donato wasn’t available for the second season and, with minimal preparation and rehearsal, Anthony Gooley was parachuted into the central role of Eddie Carbone.

Happy to say the result is a fresh triumph for all concerned. As the final blackout engulfed the theatre on opening night, the suddenly invisible cast was faced with the same prolonged silence from the audience as had occurred at the Old Fitz. That in itself is an extraordinary achievement as the distance between players and watchers – a physical separation – had been as difficult to breach as it was to focus the attention on the relatively cavernous stage.

Everything you may have heard about this A View From The Bridge remains true: it’s electrifying, mesmeric, tough, tender, intelligent, terrifying, heart wrenching. For the Old Fitz, designer Jonathan Hindmarsh condensed Arthur Miller’s working class dockside neighbourhood of Red Hook into a cross-shaped traverse with the cast occupying seats in the front rows when not part of the action. His solution for Glen Street is a bare wooden-floored island at the front of the stage, sharply lit (Matt Cox) casting all else into deep shadow. One wooden chair is the only other embellishment, until the knife.

Although the enforced intimacy of the black box is gone, the overall effect of the Glen Street staging is potent and feels equally overpowering and hazardous. The audience is not safely removed because the absence of visual distractions means the usual comfort barriers are missing. It’s exciting and unnerving by turn; then empathy and dread enter the emotional equation as the story plays out.

A View From The Bridge was first performed in 1955 in New York when post-war poverty in Europe – particularly Italy – and fear of the Cold War were causing desperate people to take any means to escape and get to America (sound familiar?). On top of that, the rise of anti-Communist McCarthyism in the USA was giving succour and official sanction to the hitherto silent bigots and paranoids – to attack or dob in a friend, neighbour or even relative. (Sound familiar?)

Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman and The Crucible are rightly considered two of the greatest plays of the 20th century, yet in this tightly disciplined, emotionally tempestuous and astute production it becomes clear that A View From The Bridge is no less a masterpiece. It is also timeless in its themes and portrait of the intricacies of human interaction and family dynamics.

The audience is let in to the world of Red Hook and what is about to take place by local lawyer/narrator Alfieri (David Lynch); he is both the watcher and the watched and the bridge between the worlds. Two illegals arrive off a cargo boat from Sicily at dead of night into rugged no-go Brooklyn, they are Beatrice’s cousins Marco (David Soncin) and Rodolpho (Lincoln Younes). Beatrice (Janine Watson) is thrilled and frightened to have them under her roof. There are stool pigeons in the neighbourhood who might betray them all, but her priority is family and doing the right thing. Her husband Eddie Carbone (Anthony Gooley) is a good man – we are told repeatedly – and is dedicated to his family, his honour and to the wellbeing of his orphaned niece Catherine (Zoe Terakes).

The two young men are eager – desperate – to work and are soon integrated into the daily routine of being picked or not for a day’s labouring on the wharves. Marco, the family man whose wife and children are hungry and hopeful back in Sicily, is a head-down, get-to-it pragmatist; Rodolpho is younger, single and full of dreams and songs. It’s not long before he and Catherine strike up a friendship that will inevitably lead to something deeper. Eddie, already suffering from impotence and the consequent sense of lost “respect”, is enraged by this development.

The performances, by all members of the company, are deeply, intelligently authentic and moving. Zoe Terakes’ innocent child-woman confirms her as one of the most exciting talents to emerge in Sydney last year, while Janine Watson’s stoic, gentle yet sinewy toughness as the wife who understands more than she should have to know is rich in another way.

The men are equally excellent: David Lynch’s Alfieri is the watchful, mostly silent and vital pointer of the moral compass for lives and a society gone awry. He is a wiser, sadder element of the audience – hard to pull off and he does it. David Soncin is perceptive in support as the decent, optimistic but ultimately vengeful Marco. It’s the least showy role though a vital element in the structure; and the structure holds.

Lincoln Younes makes much of the almost angelic Rodolpho – all smiles, inner glow and buoyant optimism. He is the sweet, bright light to which Catherine is inexorably drawn and the logic of it is impossible to deny; nor is the disaster that must follow.

And the disaster is, of course, Eddie Carbone, whose inner glow is as malignant as hell and festers beneath his lack of self knowledge and refusal to ever face himself, until it bursts forth, with tragic consequences. Anthony Gooley is a fine actor, yet stepping into the role in which his predecessor was already publicly and recently honoured must have been one of the hardest things he’s ever done. On top of that, it is one of the most emotionally demanding roles in the canon for a male actor and is the lynchpin on which the play stands or falls.

Gooley’s is a bare bones, stripped back and magnificent performance. There is no trickery, he takes no short cuts, he hides nothing. It’s also restrained, deeply nuanced and insightful. He physically transforms the man over the two hours and very little gives away how he does it. He won a Sydney Theatre Award for The Libertine (Sport For Jove/Darlinghurst Theatre), was nominated for Inner Voices (Redline), for Of Mice and Men and A Doll’s House (Sport For Jove) and in my opinion, Eddie Carbone is his best performance to date.

You have two more opportunities to catch this marvellous production. Don’t miss it.