DRESDEN

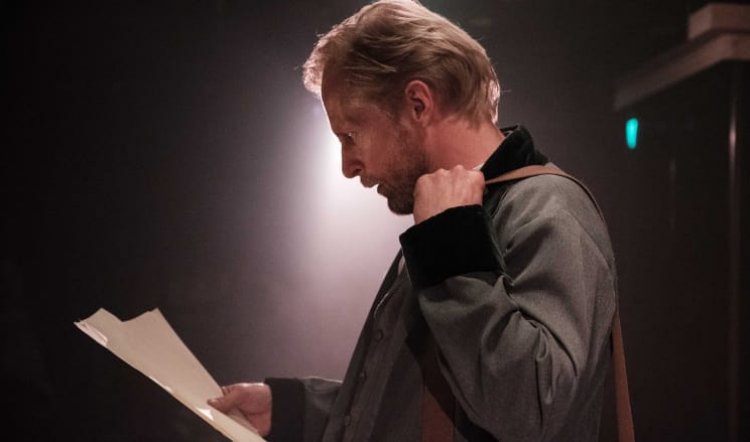

DRESDEN, bAKEHOUSE Theatre Company at KXT, 15-30 June 2018. Photography by Clare Hawley: above - Yalin Ozucelik; below - Jeremy Waters; below again - Dorje Swallow

Adolf Hitler, Richard Wagner and the city of Dresden – all connected through time and music in Justin Fleming’s new play. It opens in 1838 and closes with Hitler’s suicide via the catastrophic fire-bombing of Dresden in 1945. In between, Fleming explores the power of art and creativity – and how they can be twisted beyond recognition and their creator’s original intent.

Dresden is the city where Rienzi, Wagner’s first popular music drama (he didn’t like the term “opera” for his work) was given its premiere. It didn’t come about easily: debt and even debtors’ prison were never far behind as he struggled to make his mark. His fortunes changed somewhat when the composer Meyerbeer (Thomas Campbell) took an interest, and then entirely when King Ludwig II (Dorje Swallow) fell under his musical spell and basically funded the Wagners lavishly and for life.

The play opens with Wagner (Jeremy Waters) dictating his memoirs to his wife Cosima (Renee Lim). Elements are enacted and are both dramatic and comical – particularly when Wagner is trying to trim Rienzi from its initial five acts and six hours’ running time. The tenor Tichatsheck (Campbell again) is adamant that he will not give up a note of his role, advising instead that the intermissions should be done away with.

While an immediate popular success, Rienzi was even more influential than its composer could ever have dreamed. Heard some 70 years later by the teenaged Hitler (Yalin Ozucelik) – then an aspiring artist – Wagner’s music, philosophies and themes inspired the irretrievably mediocre maven to turn, with greater success, to national politics and world domination.

The superiority of the Aryan race is as much at the heart of the myths and legends Wagner turned into sublime music as the anti-semitism which was at the heart of their daily lives. Living on 40 years after his death, it was Cosima as staunch and unassailed keeper and stoker of his flame via the Bayreuth Festival, who firmly allied the music with the rising Nazi Party.

In reviewing Oliver Hilmes’ 2010 biography, Cosima Wagner – Lady of Bayreuth, novelist and critic Phillip Hensher wrote of the couple: “Wagner was a genius, but also a fairly appalling human being. Cosima was just an appalling human being.” A neat observation, but it overlooks her place as muse, confidante, unfailing supporter and finally, astute business woman.

And she is overlooked again in Dresden. The drama and focus naturally revolves around Wagner and Hitler – not least because Jeremy Waters and Yalin Ozucelik give riveting performances of great subtlety and understanding of the extraordinary men they play. Directed with equal subtlety and fine work with the actors (including Ben Wood as hapless yet essential Gustl) Suzanne Millar brings to vivacious life an essentially terrific play. However...

While the pivotal role of the city is dramatically pleasing and – as the harrowing accounts by survivors of the fire-bombing are related – unforgettable, it makes a triangular relationship between the two men and the city that connected them when, to be properly satisfying and entirely credible, it is Cosima who should be the third point.

As it is, in Dresden, Cosima is there at the beginning and – in a hilariously snobbish encounter with Hitler – there at the end. But she is an under-written, under-utilised enigma for the most part; left with the familiar female roles of writing down the master’s words, listening, watching, smiling and generally being virtually ghostlike in her nondescript pastel gown. Given the beautifully conceived electrifying Hitler and dynamic Wagner, it’s hard to imagine how Renee Lim could do better than she does with the shortcomings of being an afterthought or mere cypher.

That aside, Dresden is a powerful and fascinating 85 minutes. Set designer Patrick Howe makes the best of the traverse auditorium with a stylised sunken area around which the actors move – or into which they occasionally descend – and it’s lit to great effect by Benjamin Brockman with spots and colour heightening the drama and changes of place and time. The sound design by Max Lambert incorporates elements of Rienzi along with musical motifs that offer both comic relief and a welcome musical lesson for those not familiar with the ins and outs of chromatic scales.

In the end, Dresden is stirring, enthralling and surprisingly funny by turns. It highlights the fatal attraction of power and passion untempered by love and ethics. And, while based in fact, it is exhilaratingly theatrical and suspenseful even though most of us know how it ended. Recommended.