The Bourgeois Gentleman

Moliere - major French playwright of the second half of the 17th century - left a body of work that includes The Misanthrope, The Imaginary Invalid, The School for Wives, The School for Husbands and Tartuffe. Louis XIV adored Moliere despite, or perhaps even because of, the playwright’s penchant for poking fun at the excesses and pretension of his Court.

The Bourgeois Gentleman is one of Moliere’s “court plays”. A little something knocked out at the king’s request with the composer Lully, who collaborated with him on many such flummeries. And its flimsy plot and makeshift characters (save the poor sap of the title) lend credence to the idea that it was even more hastily cobbled together than usual. Nevertheless, it proved popular and went on to great success with the Parisian public and beyond.

It was dusted off and once again proved popular at the beginning of the 20th century - possibly because its main theme of ridiculing the nouveau riche would have found a ready audience in polite society where the inexorable rise and rise of those “in trade” was causing considerable unrest. Still, it’s not in the first rank of Moliere’s work, not least - to be fair - because that was never the writer’s ambition.

A pity then, that the decision was made to lavish upon it all the resources, talent, high expectations and time of the STC actors company, plus guest director Jean-Pierre Mignon, and to stage it in the large premises of the Sydney Theatre. All these factors load the play with burdens way beyond its capacity and it quickly buckles under the excess weight.

So, instead of the modest chamber frivolity it really is (ideal for the more intimate and casual Wharf 1 stage, for instance) the play - or “comedy-ballet” as it was originally and more accurately described - has the dead-weight of Major Production dragging it down. The irony, then, is that the positives - brilliant costumes, huge and imaginative set, elite actors and celeb director - become negatives because too much has been invested and it cannot repay the debt.

These thoughts are all in aid of trying to figure out why, in the face of so much talent, witty lines, visual razzle-dazzle and fun, there was - for me - a lingering sense of dissatisfaction which outweighed the chuckles and other pleasures. And perhaps why - on opening night at least - a sustained outbreak of fidgeting and wristwatch-peeking well before the end of the first half. And post-interval, numbers of empty seats whose occupants had sneaked off never to return.

Not to say there isn’t much to enjoy. For a start, the set - by Dan Potra - is one of those which, on first glimpse, achieves spontaneous applause from the audience. It’s sumptuous looking with massive drapes in knowingly mocking clear plastic, brightly lit and sparkling (Nick Schlieper) with a vast staircase across the back of the space. These stairs - descending from right to left - develop a life of their own in terms of a (literally) running gag - the funniest of the night.

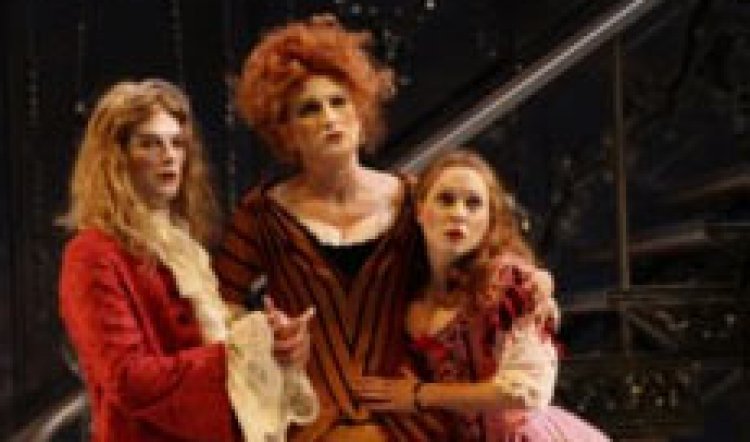

The costumes, by Julie Lynch, are spectacular. Vividly detailed period(ish) confections, they are - again - full of knowing humour and follow to the letter Dame Edna’s sage advice on how to distract an audience: colour and movement. On-stage musicians (viola da gamba, viola, violin and keyboards masquerading as spinet) fill in any gaps with Alan John’s arrangements of Lully’s original dance music.

The company is led, on this occasion, by Peter Carroll as M. Jourdain, the hopeful and hopeless social climber whose aspiration to become a gentleman, via the mercenary ministrations of self-styled masters of dance, music, fencing and philosophy, form the best part of the play. Carroll is an actor whose comic timing, pathos and sure grasp of the best-realised character hold the ramshackle “plot” together. While the early scenes between Jourdain and these dreadful men (Dan Spielman, Brandon Burke, Colin Moody and John Gaden respectively) promise so much that ultimately is not delivered. Carroll’s interaction with Gaden (a gloriously supercilious philosopher) is a particular delight - like watching two consummate sparring partners having a swing at each other.

The other characters have their moments: a heavily pregnant Deborah Mailman playing yet another lackey descends the stairs in unforgettably funny fashion, while Marta Dusseldorp turns in typically finely judged comedy as the Marquise (object of Jourdain’s adulterous fantasies) and in a tiny turn as the Tailor. The rest of the cast, however, appear to mug and struggle with the balance between comedy and caricature and most don’t bring it off; one would have to ask director Mignon why that might be.

The second half suffers most because of the inadequacy of the pivotal “ballet” scene of Jourdain’s parodic induction into the Turkish aristocracy. For a modern audience, the mix of drama and dance is always uneasy because, most often, the dancers are second-rate. That’s not the problem here, but more that the dance is neither sufficiently satirised nor seriously performed and instead, seems simply interminable and silly. It may be explained by the credit “movement director” rather than “choreographer” but is, nonetheless, misjudged, particularly as the end of the play - which follows in mercifully short order - dribbles to a close thanks to the haphazard plot.

In the late 1980s, Richard Wherrett, then artistic director of the STC, programmed a handful of hitherto forgotten Jacobean plays under the heading “Neglected Classics”. About 15 minutes into the first half of each it became clear why they had been forgotten and that they were justifiably neglected.

Almost invariably “neglected classic”, “minor classic” and “one of the writer’s lesser known works” all amount to the same lightly disguised truth and The Bourgeois Gentleman is one of the latter and proof, yet again, that we learn nothing from history - no matter how recent.

The Bourgeois Gentleman, Sydney Theatre to December 9; ph: 9250 1777; www.sydneytheatre.com.au

-c444x300.jpeg)