KING CHARLES III

KING CHARLES III, Sydney Theatre Company presents the Almeida Theatre Production at Roslyn Packer Theatre, 2 April 2016. Photography by Richard Hubert-Smith.

According to playwright Mike Bartlett’s program note, he thought about writing King Charles III in cod Shakespearean verse but as he found the notion “terrifying” (a 21st century talent up against the greatest genius of English-speaking drama) it was “enough to stop me writing a word.”

It was therefore some while before director Rupert Goold got wind of the idea and “…for two years the play remained merely a good idea – unspoiled by any attempt to write it into reality.” And then he did. In April 2014 it became a smash hit for the Almeida Theatre (sort of Belvoir in north London) before transferring to the West End and Wyndham’s Theatre and the ecstatic reviews that now decorate taxi backs, buses and the poster panels outside the Ros in Sydney.

These reviews (bits of them anyway) are splattered with stars and include such enticements as “Bold, brilliant and unstoppably entertaining. Theatre doesn’t get much better than this.” ★★★★★ The Times. “Thought-provoking, serious fun.” Financial Times. “Theatrical dynamite.” Time Out London and “The most spectacular, gripping and wickedly entertaining piece of lèse-majesté that British theatre has ever seen.” The Telegraph. And so on.

The play was then sent on tour around the provinces with a touring cast while the original transferred to New York for a limited run where it picked up more lavish praise: “A gripping evening of theatre, a rare contemporary play with real tragic vision, and easily the sharpest, most sophisticated political drama I have ever seen on stage.” Time magazine (declaring it the play of the year). “Splendid, high-reaching and utterly unexpected.” The New York Times. That paper’s critic Ben Brantley also declared it “a modern masterpiece in New York Times best theatre of 2015. While Time Out New York said “Galvanizing and astonishing.”

Why then, on its long-awaited Sydney opening as one of STC’s annual overseas visitors did I find it disappointing and underwhelming? The inevitable let down of over-anticipation and hype, perhaps? Possibly, but looking back on this same slot in previous years, both Steppenwolf’s August Osage County and Olwen Fouerre’s riverrun lived up to expectations and more. For me, King Charles III did not.

Yet according to the ads, the production is decorated with more 5-stars than you’d find on the epaulettes of a cartload of generals. The clue lies in a quick Google and Wikipedia search: the ads and multiple 5-stars refer to the West End and New York cast. It’s back to the future for the colonies and the provinces: we’ve got the touring cast and crucially, that means Robert Powell instead of Tim Pigott-Smith as Charles.

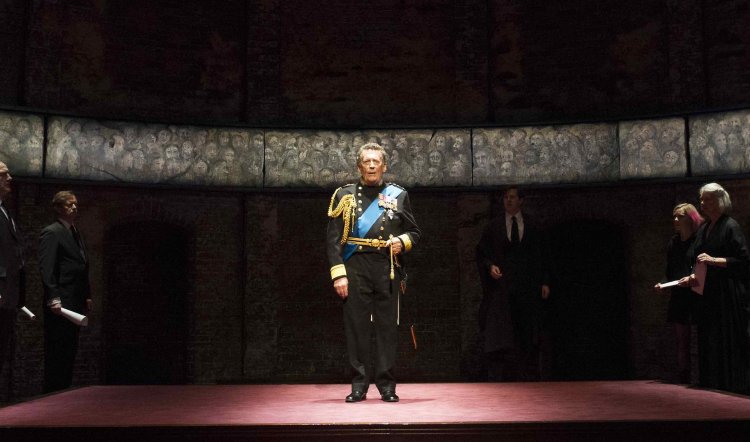

Now, while it shouldn’t matter that Powell is the same un-regal height (177cm) as Prince Charles while Pigott-Smith is a more majestic 183cm, it does matter that Powell appears to have been lumbered with the latter’s costumes – without alteration – so he resembles not an ageing yet debonair would-be monarch so much as someone who’s been kitted out, sight unseen, from a factory outlet.

And he, along with others in the cast deliver similarly ill-fitting performances. Some bellow, most gabble as if speaking with mouths full of marbles: at this level and at these prices it shouldn’t be necessary to have to work out what an actor is saying. A display of rare conviction and credibility is Tim Treloar – channeling the late Neil Kinnock who was the best Welsh PM Britain never had – as blustery Labour prime minister Tristram Evans. On the other hand, it’s impossible to know whether Beatrice Walker is simply appalled by the silliness of the role of Princess Diana’s Ghost (Shakespearean – geddit geddit?) without knowing if Katie Brayben (West End) and Sally Scott (New York) appeared to be equally daft in drifting about the stage being harbingers of future shock.

The play opens stirringly with a beautifully staged and emptily symbolic funeral of Elizabeth II amid processional choruses (Jocelyn Pook composer; Belinda Sykes musical director; sound Paul Arditti). The empty dais where the catafalque would stand is flanked by tall white candles, black-clad mourners and rimmed on high by a suggestion of watching faces (design Tom Scutt). Throughout the two hours 45 minutes it remains the focus with only a desk, a couple of benches and changing lighting states to indicate location and passing time (lighting Jon Clark).

Much as one might expect from the arrogant yet well meaning Charles, his first act as (as yet uncrowned) monarch is to disagree with the Prime Minister. He refuses to apply his signature to a Bill to restrict press freedom, apparently in response to the Milly Dowler v Murdoch atrocity. The constitutional, political and social crises that arise from the missing signature are the meat and raison d’être of the play and it’s a somewhat flimsy if piquant premise.

Side plots (Bard nods again) are provided by Prince Harry (Richard Glaves) developing a social conscience and a passion for art student Jess (Lucy Phelps) who has pink and blonde hair and “a past”. At the same time his elder brother William (Ben Righton) mooches about, hands in pockets while wife Kate, Duchess of Cambridge (Jennifer Bryden) takes on the Lady Macbeth role and schemes with ambitious intent.

What transpires clearly shocked polite London and galvanised Royal-worshipping NYC but should come as no surprise to Australians, accustomed as we are to having our elected government sacked by a British monarch. On the one hand, it’s an interesting premise and occasionally – if cheaply – funny. On the other, it’s a demonstration of why Australia really should snip the apron strings.

As a political drama and satisfying theatre King Charles III was somewhat shackled by all the above plus under-cooked performances. (Tony Llewellyn Jones was in the opening night audience and should have been on stage as Charles, while an A-list of Sydney actors, including Richard Roxburgh, Hamish Michael and Kate Mulvany were also twiddling their thumbs, whereas all – and a dozen others – could deliver the blank verse with greater skill and aplomb than the visitors.)

Most of the opening night crowd was appreciative, however. There was one whistler and some stompers among them and two curtain calls. Nevertheless, the campaign of ★★★★★ ads and snippets of superlative reviews for a cast that was not at the Ros must have been influential in the enthusiasm. It left me lukewarm if not exactly cold.