CLOUD NINE

CLOUD NINE, Sydney Theatre Company at Wharf 1, 1 July-12 August 2017. Photography by Daniel Boud, above: Heather Mitchell and Josh McConville; below: Harry Greenwood, Anita Hegh and Kate Box; below again: the company in the conservatory with the pianoforte

When Caryl Churchill’s Cloud Nine was first staged at the Royal Court in 1979, shock waves rippled across a city which had until recently taken for granted that it was “with it” and still the centre of the universe. The consternation was because she had written an excoriating farce about what she later described as, “Genet’s idea that colonial oppression and sexual oppression are similar”. And despite almost a decade of bloody Irish struggle on its streets and the rise of “women’s lib”, polite society was gobsmacked. Feminists and the enlightened guffawed with delight; the Establishment harrumphed and their wattles shook with rage.

Context is everything: London in 1979 was in the aftermath of the “winter of discontent” – when the unions fought James Callaghan’s revisionist Labour government to a futile standstill. It caused fuel and food shortages, power rationing, blackouts, long strikes while uncollected garbage rotted on the streets and the dead were unburied for weeks – it was the coldest winter in decades, so that wasn’t as bad as it could have been. Nevertheless, it was bliss for the Conservatives and Margaret Thatcher came to power on an otherwise beautiful spring day in May. (And would become a character in Churchill’s next classic, 1982’s Top Girls.)

British government(s) were also in the midst of their last colonial war – the only one to be fought in the Mother Country – as the IRA persisted through more than a decade of bombings. In February, the more radical INLA (Irish National Liberation Army) infiltrated Parliament itself and blew up Airey Neave, formerly Thatcher’s shadow minister for Northern Ireland. Later that year, the IRA blew up Lord Mountbatten and his family on their Irish holiday fishing boat – finally, class warfare was added to the mix.

Then, starting with the characters of Clive (Josh McConville) and his wife Betty (Harry Greenwood), Caryl Churchill blew up the long-treasured images of British Colonial rectitude and power and turned theatrical conventions upside down. Cloud Nine opens somewhere in Queen Victoria’s Africa, where imperial functionary Clive is a pompous, priapic ass. In his view the Natives are revolting, and the sight of his lover the splendid Mrs Saunders (Kate Box) flourishing a riding crop, is enough to give him a permanent erection.

This is the Empire on which the sun never set and Clive’s uppity black servant Joshua (white actor Matthew Backer) is in his own mind more British than British, declaring “My skin is black, but my soul is white. I hate my tribe...” Meanwhile, poor silly Betty hates herself and longs to be what any man would wish for – a man, of course. Through the hapless wife Churchill underlines that Betty’s “femininity” is a male construct; she also goes on to subvert gender and racial stereotypes, long before it became fashionable to do so.

Churchill destabilises other shibboleths too: Clive’s best friend, the explorer Harry Bagley (black actor Anthony Taufa), is a spiffing chap whose mere presence sets ladies’ hearts beating and parts moistening. Yet as a Man’s Man he’ll fuck anything that moves – including Clive and Clive’s young son Edward (Heather Mitchell) who’s potty about his Uncle Harry.

Edward is a poignantly Peter Pan-like figure: a girl-boy and a girlish boy who’s hopeless with a ball and whose beloved rag doll is subjected to paternal disgust. His love for Uncle Harry is as unnerving now as it was when first written: “You know what we did when you were here before. I want to do it again. I think about it all the time. I try to do it to myself but it’s not as good...”

To laugh and gasp simultaneously is the pattern of audience response. Polymorphous perversity abounds as do hooped crinolines as Betty’s solicitous mother Maud (Anita Hegh) clucks like a passive-aggressive hen; Kate Box meanwhile performs miracles of quick-change from the rampant widow Saunders to demure nanny Ellen whose passion for Betty can only end in tears.

The second half of this lengthy but brilliant play is set on Clapham Common in the summer of 1979. By this time, the revolting Natives are the Irish but the moral order and the characters are inverted once again. Cloud Nine prefigures “fluid sexuality” and multiple gender identities not only in its casting directives but also in the way the characters of the first half return in the second – same same but different.

Churchill’s intricate weave has characters sharing names, histories and bodily fluids in the dying days of Swinging London. Although a century has passed, they have aged only 25 years, yet their personal-political concerns are of 1979; at which point – in the real world – the patriarchy had been given an ironic boost by the election of the country’s first female PM.

Nevertheless, female power and sexuality is the subverted focus of Act 2 as Matthew Backer returns as the homosexual freebooter Gerry. Like so many gays of the pre-AIDS period, he trolls the Common at night for casual sex while his live-in lover, the now adult Edward (played by Harry Greenwood with all the “feminine” and wifely qualities displayed by his mother/himself in the first half). Josh McConville returns as a small girl, while Kate Box and Anita Hegh are lesbians divided by class. It’s a sequence of relationships and political points that just about does your head in – particularly as contemporary gays and lesbians rush to grab a slice of the patriarchy (ie, marriage).

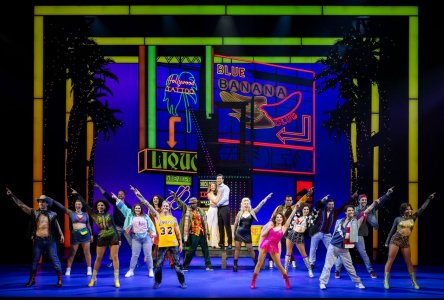

Cloud Nine is played on a black-walled set where a brightly-lit white-framed “conservatory” is the only relief, the floor is fine soil the colour of dried blood (and in the second half: acres of green grass). It’s another fine achievement by director Kip Williams, who understands the play to thrilling effect. He’s cast it beautifully, orchestrates the actors with finesse and each is released into disciplined freedom to play to his and her individual strengths: they’re all wonderful.

The creative team of designer Elizabeth Gadsby, lighting designer Alexander Berlage, composer Chris Williams and sound designer Nate Edmondson has produced a place that is fresh, acute and timeless – as is the play. The Brits were very good at colonising – the world, women and the Other – and it’s still happening, globally now, and that’s what Cloud Nine is about.

Consider this: British colonial history apparently doesn’t figure on the UK school curriculum. And a YouGov survey in 2016 found that 44% of respondents were “proud of Britain’s history of colonialism”, 21% regretted it and 23% couldn’t give a toss. Asked whether the British Empire was a good or bad thing, 43% said “good”, 19% said “bad”, while 25% shrugged and went out for a curry.

Cloud Nine: absolutely recommended for loads of laughs and clever stuff.

-c444x300.jpeg)