SYDNEY FESTIVAL - THE BOYS

THE BOYS, Griffin Theatre at the SBW Stables Theatre, 6 January-3 March 2012; photos Brett Boardman: Jeanette Cronin and Josh McConville; Johnny Carr and Josh McConville.

WHEN Gordon Graham's The Boys was first staged by director Alex Galeazzi at The Stables in 1991, Sydney was still reeling from the hideous gang rapes and murders of Anita Cobby in 1986 and Janine Balding in 1988. The aftermath – the harrowing trials and eventual convictions of "the boys" in both instances – and what was revealed in those trials about them and what they did, caused continuing shock waves of bewilderment and horror throughout the community. Why? Who were they? What made them do it? What made them? These questions and more were almost visible in the air in the decade following those brutal killings and both young women – the nurse-beauty queen Cobby in particular – came to symbolise goodness and innocence versus mindless, violent evil.

In 1998, the play was adapted for the screen by Stephen Sewell and has become one of the legendary movies of the modern Australian industry. It made David Wenham a star and continues to haunt audiences with its depiction of the toxic, twisted "love" between the brothers and their mother and girlfriends and its dire consequences. In 2003, the exhibition Anita and Beyond, at Penrith Regional Gallery, stirred the somewhat settled silt of public imagination again with a series of works by 12 artists, including Adam Cullen. It aimed, in the words of Anne Loxley, the SMH art critic of the time, "…to tell personal stories that examine the realities of life after violence, in an attempt to heal …the sober, sensitive exhibition conveys a sense of the real Anita, interrogates her place in Australian mythology, forcing unanswerable questions about humanity."

Much the same can be said of Graham's play – now tweaked and updated by the playwright in collaboration with its current director Sam Strong . It's as fresh and shocking as the (in)famous portraits by Cullen from Anita and Beyond that currently dominate the Stables foyer and is possibly even more potent and relevant today when domestic violence, street violence and sheer bloody-minded unpleasantness seems to be even more prominent in everyday city life than it was just two decades ago.

Of The Boys – about three homicidal brothers and their family – Graham recently told Steve Meacham in the SMH: "I've always denied it was based on the Cobby case but I guess it was prompted by it. Not so much by the details of the murder but the public reaction to it." And the reaction was a mixture of fascinated revulsion and disbelief: how could seemingly ordinary young men, with girlfriends and a loving mother, commit such appalling, savage crimes against a complete stranger?

Gordon Graham sets out to explore those questions and devise some answers in The Boys by telling the back story. Over intercutting periods of time – a single day and a couple of months – he paints a vivid psychological picture of the brothers Sprague. And with stunning plausibility, how they came to be caught up, individually and collectively, in the deadly spiral of noxious emotion and impotent rage that led them inevitably to disaster.

Brett (Josh McConville) is the eldest and just released after a year in jail for assault and battery; his brothers Glenn (Johnny Carr) and young Stevie (Anthony Gee) are preparing to celebrate his homecoming with a barbie and an eskie full of ice and VB in their wretched suburban backyard. Waiting at home are their adoring mother Sandra (Jeanette Cronin), Brett's faithful girlfriend Michelle (Cheree Cassidy) and Stevie's pregnant girlfriend Nola (Eryn Jean Norvill). At first absent but a dominating figure nevertheless is Glenn's socially ambitious girlfriend Jackie (Louisa Mignone).

Subtly and without judgment or didactics, the play sketches the underlying motives and sentiments that propel each member of the family through the perpetual train wreck of their lives. And gradually the sketches are filled out and coloured in until the lines and dots are joined and the picture emerges. It is both compelling and horrible – not unlike the Cullen portraits of the killers.

In 1970, Germaine Greer observed in The Female Eunuch, that "women do not realise how much men hate them, and how much they are taught to hate themselves". She could have been talking about The Boys, but of course, it's a universal – not confined by class, culture or era. As Brett quietly rages like a volcano about to erupt, his impotence is not only sexual but also about male jealousy and warped male pride. He has been raised to believe that his manhood and masculinity depend on the power of his penis and that his penis is magnificent and a weapon. When it isn't working – literally or figuratively – he is reduced to humiliated, bemused rage with one ambition: to punish those responsible for his pain.

Paradoxically his youngest brother, the gormless, overgrown child Stevie, is an equally dangerous concoction. Sullen and relatively harmless on his own, in the company of his elder brothers he is like an emotional Hulk, bursting out of inadequacy into dumb wrath and barely suppressed violence.

In the middle of the trio in more ways than one, Glenn very nearly escapes his fate through Jackie's strength and intelligence. She is the classic working class aspirant and very nearly drags him with her, but ultimately the pressure applied by his brothers is too strong; and he is too weak. And all three are lionised by their weak-minded mother Sandra: this is an instance when it really is the mother's fault. Except, of course, she has no idea and has no idea how manipulative and destructive her "love" is.

Nevertheless, the Greer opus of 1970 is merely the most recent light to be cast on male-female conflict. In 1487 the Catholic Church (oh what a surprise) dreamed up Malleus Maleficarum – the Witchcraft For Dummies handbook commissioned by the hilariously named Pope Innocent VIII. To the monks and priests of the Church, powerful women were sexy, scary and dangerous (plus ca change). Something had to be done about the effect they had on helpless men. In a chapter entitled: How They Deprive Man of his Virile Member, witchcraft was described as coming "from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable" and witches were identifiable by various means including their penchant for eating newborn babies, copulating with the devil, making men impotent and so on.

In an online transcription of this virtual Witchcraft 101, two convicted witches are described thus: "These two could, whenever they pleased, cause the third part of the manure or straw or corn to pass invisibly from a neighbour’s field to their own; they could raise the most violent hailstorms and destructive winds and lightning; could cast into the water in the sight of their parents children walking by the water-side, when there was no one else in sight; could cause barrenness in men and animals; could reveal hidden things to others; could in many ways injure men in their affairs or their bodies; could at times kill whom they would by lightning; and could cause many other plagues, when and where the justice of God permitted such things to be done."

If the last sentence is puzzling, it's no more so than the rest of this misogynist drivel. It would be almost funny if so many millions of women throughout history and around the world had not been tortured and killed in the cause of male insecurity and hatred. And still are being tortured and killed, every day – let's not forget.

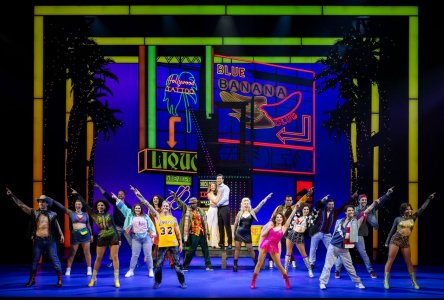

So … the fact is that Gordon Graham's play and Sam Strong's production of it are compelling, convincing and brilliantly realised by a cast that should be described in the same terms. Designer Renée Mulder, with lighting designer Verity Hampson, have done away with the original two locations – inside the Sprague home and in its backyard – in favour of a single area of parched grass with Hill's Hoist, beaten up lounge and armchair and broken down corrugated iron fencing that is beyond soulless and somewhere near ominous. Composer Kelly Ryall adds to that sensation with a soundscape that's both threatening and insidious by turns. And the underlying sense of impending doom and violence (very little eventuates onstage, it's mostly suggested) is like an imminent thunderstorm whose presence is signalled and choreographed by fight director Scott Witt.

The Boys is a classic and its depiction of the causes and consequences of male violence, misplaced notions of power and the dark side of the precious family unit could easily be transposed to anywhere and any community where women are impoverished, ill-educated and without hope or opportunity. And anywhere that men are born with expectations of power but not the responsibility that goes with it – try the north of England, the Deep South, indigenous Alice Springs, for instance.

Why is the play so rarely performed? All the above is probably the answer. Meanwhile, The Boys is one of the most fiercely entertaining productions you're likely to see this year. Unequivocally recommended.

-c444x300.jpeg)